1a. Creative Writing in the UK (in English)

Dr Derek Neale – Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing, The Open University

In Suman’s presentation he talked of publishers once acting as gatekeepers to literary production, suggesting that this role was now under threat and was liable to be usurped to an extent by the editorial and self-publishing potential of the internet. I would add that the university and the creative writing workshop within the university – especially in the UK and US – have come to act as a similar sort of gatekeepers with regards pre-published work. Creative writing programmes can perform some editorial functions that publishers used to undertake, and some of the pre-selection tasks before publication. Publishers now often select writers on the basis of accomplishment on such courses, as often evidenced in course publications (i.e. anthologies of student work are often sent to agents and publishers; meetings between industry professionals and students are often arranged as part of the teaching). That is one of the consequences of creative writing study.

For this presentation I will give a broad introduction to Creative Writing because I suspect it is less familiar as a subject area to many – some might query if it is part of English Studies at all. I will largely leave as implicit its more obvious connections to the aims of this collaboration and project – entrepreneurship and the common good - because I’ve a lot of exposition to cover. But some points I will at least start to draw out.

What is Creative Writing?

Creative Writing is a relatively young term, first arising in the mid-nineteenth century, and one that has come to describe writing, typically fiction or poetry but also script, which displays imagination or invention, often contrasted with academic or journalistic writing.

It has been used in this way most prominently since the 1920s, and has become used as the term for a specific strand of university and pre-university study. In the UK the rise of creative writing has been one of the biggest developments in the study of literature and language over recent decades. It offers a practice-based approach, a factor which is its self-defining and distinguishing feature.

It is often associated with English Studies departments, although not exclusively. By comparison with much English literature and language study – which engages mostly in retrospective analysis and theoretical consideration of historical or contemporary literary artefacts or language usage – the academic discipline of creative writing is primarily concerned with participation in the act of writing.

Such study is assessed via the students’ literary outputs, but it often also involves reflective commentaries about the process of writing. These are subsidiary components to the main output, which is writing in one or more of a number of genres: fiction, poetry, creative nonfiction (memoir, biography, travel and nature writing, for instance), as well as scripts for a variety of media – film, radio, stage and new media. In many ways it is similar in its practice-based ethos to the disciplines of art, design, dance or performance, more than either English language or literature study, in that experience of the creative process is the central focus. Yet the currencies of English studies – language and literary artefacts – are also prime tools in Creative Writing’s active study, its ‘canvas, colour and back catalogue’ if you like.

Who are Creative Writers?

This list offers just a quick sample – writers who have either taught or studied creative writing or both. Some of them you might have heard of, some not:

You’ll note that there’s a Brazilian in this sample list. I’ll come back to him at the end – and explain.

These writers have made, and many continue to make, money from writing – but many of them have also earned money from teaching. Creative Writing is traditionally taught by practitioners. Markets in literary artefacts and literary education appear often to be co-dependent, but also to implicate the broader range of creative industries. The level and mode of writers’ earning activities can sometimes be surprising. For instance, Malcolm Bradbury who with Angus Wilson set up the first and most prestigious UK Creative Writing programme at UEA, wrote novels and a considerable amount of literary criticism, but also, while holding an academic post, scripted many episodes of the popular UK TV crime series Frost - as well as several other TV dramas. Some of the writers above – notably Fey Weldon and Joseph Heller – had profitable careers as copywriters. Many, probably most, of the above have written journalism, and not just reviews.

The Writing Program at Iowa, the US’s most longstanding and prestigious Creative Writing establishment has had a working association with tens of Pulitzer prize-winning authors – former students and tutors. In the UK, UEA – or the University of East Anglia to give it its full name - can list many Costa Booker Prizewinning authors as former students and tutors – some feature above.

But it has to be said that Creative Writing is not just about the headliners, the named successes. Creative Writing is one of the most popular subject-areas and encompasses many, many levels of intent, approach, ability and achievement.

Why Creative Writing?

Why does Creative Writing appeal to HE students – and indeed to non-university students? At the Open University we have a Start Writing Fiction MOOC (mass online open course) that has attracted 200,000 would-be writers in the last two years. Such popularity is typical. The course has had 8 presentations at an average of 25,000 students per course. Many students have done the course multiple times – they use it as an ongoing workshop. Nearly 2,000 students have studied the course on all 8 presentations. This challenges the usual linear notion of teaching and learning. The websites also stay live and I’ve seen students still active, writing and posting work on a course website 2 years after the course has officially finished. This is an introductory and pre-degree level course; it is free, online and open for anyone to take. The next presentation starts on April 24 but it is possible to join at any time after the course has started: if you want to take a look, go to - https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/start-writing-fiction

Creative Writing students have many motives for starting to write. Some will be drawn by the transferable writing and reading skills, by the promise of being able to generate and develop new ideas. Some will want to be professional writers, though as the novelist Rachel Cusk says, this might be fewer than suspected:

Cusk also says:

Writing by this token is not solipsistic, autobiographical or therapeutic. Students may be writing genre fiction and not about themselves at all. But it is a personally chosen endeavour – not necessarily one of ‘enterprise’ in the business sense or with profit as its major goal. The occasional writer can profit from the activity, yes – and university accountants tend to see too readily the likely profits accruing from such a popular subject. But it is often true that students have a sense of vocation. As cohorts they tend to perform above expectations – there is evidence for this not in just isolated and prestigious universities but nationally, across the UK and all universities providing creative writing study.

English and Creative Writing – how do they fit?

Within Creative Writing study, all aspects of the creative process feature under the ‘practice’ heading. Besides craft, form and technique, other aspects include the generation and development of ideas, the ability to read as a writer, and pragmatic elements such as using a notebook and editing at various levels – the level of sentence, line, paragraph, scene, stanza, story and chapter.

Reading as a writer means reading with close scrutiny. This is where it fits well with English Studies. It focuses on how writing is built and made, on how form relates to content. It involves research of literary, social, historical and cultural contexts. It involves close reading of established works and also work in progress, often including the work of peers in writing workshops or online equivalents. As Cusk says:

The rise in creative writing study in UK universities from 1970 onwards (from 1930 in the USA where the subject originated) – and the accompanying steep rise in writers facilitating such study – can be seen as ironic, contemporaneous as it was with certain propositions in literary criticism which suggested the author was no longer necessary for the interpretation of texts (see essays such as Roland Barthes’ ‘The death of the author’ and Michel Foucault’s ‘What is an author?’).

Malcolm Bradbury commented on his double identity as Literature academic and writer:

But there is an unlikely fit between theory and practice. Neither critical theorists nor Creative Writing teachers hold much tolerance for what might be termed the ‘cult of the author’, in which the writer is seen as genius or mysterious progenitor of texts, their inscrutable talent and distinctive biographies lending them almost divine legitimacy. In the era of the workshop, writing has come to be seen as a question of endeavour, routine and assiduous editorial attention, with more emphasis on creativity as process, on technical and practical consideration of the drafting regime, and on the faltering, often inelegant bravery of first drafts.

In the commercial world of publishing there is a resilient fascination with authors, especially the bestselling and canonical variety. However, within Creative Writing there is a focus on the phenomenology of writing practice, with emphasis ‘on creativity as a dynamic process as well as on creativity as a completed product’ (Carter, p. 340) – and concurrently in Literary studies there is a revived critical and archival interest in the effect of editors on literary output (for instance, in work on Raymond Carver, William Golding and Jane Austen). With this new focus there has been a common, if not exclusive, shift in terminology towards the term ‘writer’ and away from ‘author’ (and its connotations of authority).

It should also be noted how Creative Writing has influenced critical English. ‘Interventionist’ approaches to linguistic and literary analysis have gained greater credence, with the rise of transformative forms of analysis whereby the reader intervenes as writer in the original text. As Carter explains it, ‘[r]ewriting involves making use of a different range of linguistic choices’ in trying them out, one also thinks through their properties and implications.

Rewriting can consist of re-centring a scene or chapter by, for example, writing in the voice of a peripheral character, writing in a different tense or grammatical person, or by changing the geographical or historical setting. There are numerous possible interventions and, as Carter suggests, this approach has a relationship with both creative writing and critical analysis; it is a more active mode of reading and participating in a text ‘along a critical–creative–reading–writing continuum’ (p. 342).

It should be noted here that on that continuum there are notable literary outputs that in different ways become post-colonial or other kinds of critiques of original works. For instance, Peter Carey’s novel Jack Maggs which has Magwitch from Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations as its main character, and Jean Rhys’s novel Wide Sargasso Sea which is a fiction with Bertha (Christophine) from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre as its main character. This might even prompt more rewriting - see for instance, Polly Teale’s play, After Mrs Rochester which incorporates Brontë’s and Rhys’s characters, as well as Rhys’s life story.

Is Creative Writing rising?

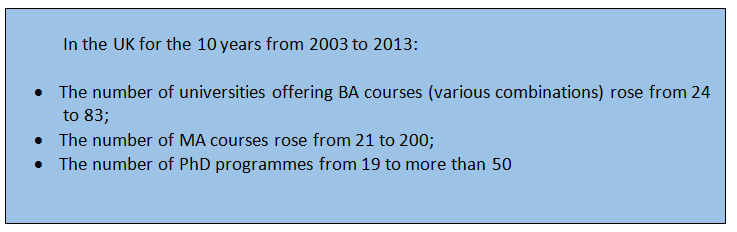

In the US the subject was seen initially and predominantly as MFA-level study. In the UK it was initially seen as an MA-level subject – following the launch of the MA programme at UEA with its first (disputed) student – Ian McEwan, and the launch of similar programmes such as at Lancaster University around the same time. The amount of Creative Writing provision at all levels has since accelerated at a fast rate.

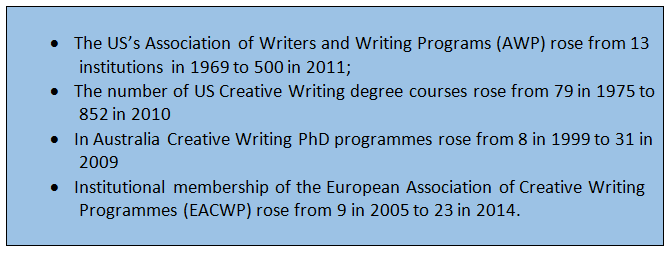

This growth is still accelerating – and is no longer confined to MA provision. This isn’t just a UK phenomenon. It follows a comparable rise in the US and other countries:

What is Creative Writing Research?

The most common mode of Creative Writing research is creative practice – often referred to as ‘practice-based research’. The researcher explores, articulates and investigates via his or her practice – the writing of poems, short stories, novels, creative nonfiction, plays and films. The creative outputs and artefacts in themselves involve research, as do their formal considerations. Practice is central, ‘critical or theoretical understanding is contained within, and/or stimulated by, that practice’ (NAWE p.11). Some results of practice-based research can include critical works, and the critical elements can be connected to, or stand relatively free from, the practice that informs them.

The Creative Writing PhD student typically writes a book-length work together with an accompanying critical commentary which focuses on aspects of the contextual analysis and investigation. The first UK Creative Writing PhD student was at UEA in 1990 - Fadia Faqir, a Jordanian writer whose first novel Nisanit had been written as her MA dissertation at Lancaster. Since then PhD programmes have become increasingly common in the UK and Australia, but not in the US where the Master of Fine Art (MFA) remains the predominant top-level qualification in the subject.

As you have seen from the list of Creative Writers, the canon has come to be influenced, informed and affected by Creative Writing. Style and form have also been affected. For instance, the short story - often the modus operandi in creative writing study; the workshop has become the short story’s stylistic studio. Ian McEwan produced a book of short stories in his MA year – First Love, Last Rites.

And there has been experimentation. The second-person story, for instance, has proliferated in the workshop era. This could be attributed to the workshop where a second-person narration is often used in exercises, demonstrating different approaches to point of view while also illuminating everyday linguistic gradations and combinations of intimacy and imperative command.

Lorrie Moore’s Self-Help short story collection (1985) is perhaps the apogee of the second-person story. All in the second person, its stories parody the self-improver’s instruction manual. The collection was written for Moore’s Creative Writing MFA dissertation, its stories emanate from the poetics of the workshop. Yet on a commercial level, the headliners are again misleading. The short story collection is commonly reputed to be disliked, ignored and never taken up by publishers. Moore and McEwan are the exceptions. Short stories might be a natural output of the workshop, but collections don’t sell and there are fewer and fewer venues to publish individual stories.

This is another example of the way in which Creative Writing outputs are often mismatched with possible commercial or even literary outlets. Stories are not commercial or viable as potential for a business plan, say, or a career opportunity (though some notable writers have indeed made their living from short stories). Poetry, in general, would offer a similar example. It is all but impossible to make a living from publishing poetry alone (though again there are notable exceptions).

Creative Writing – earnings and entrepreneurship

The incompatibility between some of the literary outputs from Creative Writing and the commercial market is striking. For instance, the Barbican Press was set up (by Professor Martin Goodman based at the University of Hull) to publish some of the often-rejected but nonetheless critically worthy novels produced on Creative Writing PhD programmes.

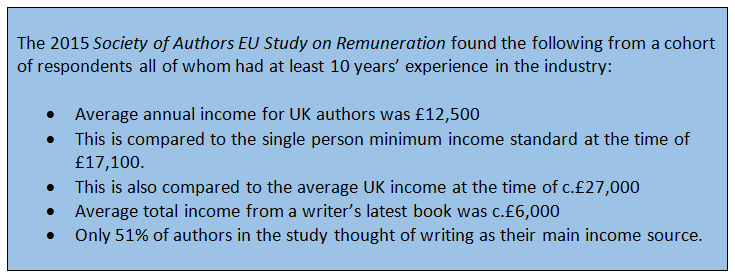

But there are many commercially published works arising from Creative Writing MAs and PhDs (and some too from undergraduate study). For instance, consider two current students as examples. Both have written more than one previous novel and are writing their next novel as part of a Creative and Critical Writing PhD. Both have been relatively successful – both have had their previous work translated into several languages, both have met with critical acclaim. They are more than likely to receive an advance fee for publication of their PhD novels. But that advance fee and proceeds from publications, while substantial by comparison to any academic publishing deal, will probably not be big enough to live on. It is fair to say that neither student could survive on their writing alone. Yet both were successful graduates of the UK’s most prestigious Creative Writing MA programme – they are near the top of the range of achievement within the subject area, and are well established professionally.

The figures above suggest that most writers by definition have a portfolio of occupations. This other work includes teaching, journalism, translation, subtitling, copy-editing, copywriting, working in the creative industries and a whole range of other part and full time employment.

Some university Creative Writing departments (for instance, Bath Spa) plan and teach towards this eventuality. They ask their students to engage in external contacts (in their final undergraduate year) – with businesses, venues, schools, publishers, publications. Students are required to write business plans whatever their venture. The student projects range from writing classes in the community, to publishing a local events magazine, to arranging international events. Some projects don’t necessarily involve writing. Some projects can lead to long-term business ventures and/or direct employment.

But these business-focused aspects of study are relatively rare. Overall, for many, Creative Writing study is a unique period of dedicated, concentrated focus on writing (and reading), which is not repeated in working life – should the student progress to some level of ongoing practice.

Entrepreneurship features in both the inventiveness and innovations of the portfolio combinations, some of the ventures engaged in, but also in the way writers manage to continue to write. Some form small publishing presses, for instance. Many are part of ongoing writing workshops and self-formed organisations outside of official study. But much of this isn’t entrepreneurship in its conventional usage. A sometimes used portmanteau term has risen to greater prominence in the past few years – social entrepreneurship. Many of the initiatives and commissions that fit into a writer’s portfolio of work might fall under that heading – including writing residencies in prisons, in care homes, with refugees and asylum seekers, or with other sections of the community, but also other initiatives involving the community and the use of language and art in some way. These are readily identifiable and newly emerging roles, often set up in collaboration with existing bodies. Such roles are increasingly seen as compatible with the knowledge and skillset gained by writing students, and students of literature.

Footnotes

Creative Writing study at the Open University is delivered by between one and two hundred associate lecturers, all of whom are practising writers. The Open University Tutor Blog reveals some of their publications but also some of their ‘other’ work. See: http://www.open.ac.uk/blogs/WritingTutors/

As discussed earlier in this presentation, some writers’ other work is involved with the media and at the Open University we have several collaborations with the BBC that link with Literature and Creative Writing – Nicky mentioned one, the Secret Life of Books, in her presentation. We have also just collaborated on a biographical film on the lives of the Brontës – To Walk Invisible https://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/culture/literature-and-creative-writing/literature/walk-invisible-interview-the-crew which provided research resources and teaching resources for our students – for instance, interviews with the film crew, scriptwriter/director about uses of language and the methods of writing for screen. Another collaboration was Paperback Heroes – which provided teaching and research interviews with several best-selling authors, including Neil Gaiman and William Boyd. See: https://www.open.edu/openlearn/tv-radio-events/tv/sleuths-spies-sorcerers-andrew-marrs-paperback-heroes

And so to the Brazilian writer I mentioned earlier. One other collaboration the Open University has in relation to its creative writing activities is with BBC World Service – the OU co-produces a biennial international radio playwriting competition with the BBC. One of this year’s winners was Brazilian – Pericles Silveira. His radio play: The Day Dad Stole a Bus. Because of the collaboration, our writing students have benefited from having privileged access to this play, the scripts and interviews with writer and director: https://www.open.edu/openlearn/playwriting

References – and items that have informed this discussion

Bradbury, M ed. (1995) Classwork London: Sceptre

Carter, R (2011) ‘Epilogue – Creativity: postscripts and prospects’ in Creativity in Language and Literature: The state of the Art eds. Swann, J, Pope, R and Carter, R. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cowan, A (2016) ‘The Rise of Creative Writing’ in Futures for English Studes: teaching language, literature and creative writing in Higher Education ed. Hewings, A; Prescott, L; Seargeant, P. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cusk, R (2013) ‘In praise of the creative writing course’ in The Guardian 18 January.

Holland, S (2003) Creative Writing: Good Practice Guide Edgham: English Subject Centre.

McGurl, M (2009) The Program Era: Postwar Fiction and the Rise of Creative Writing Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP.

Munden, P (2013) Beyond the Benchmark: Creative Writing in Higher Education York: HEA www.heacademy.ac.uk/assets/documents/disciplines/English/HEA_Beyond_the_Benchmark.pdf

NAWE (National Association of Writers in Education) (2008) Creative Writing Subject (Teaching and Research) Benchmark statement www.nawe.co.uk/writing-in-education/writing-at-university/research.html

Neale, D (2016) ‘Creativity and Creative Writing’ in Creativity in Language eds. Demjen, Z and Seargeant, P. Milton Keynes: OUP

Open University FutureLearn Start Writing Fiction MOOC https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/start-writing-fiction

QAA (2016) Creative Writing Subject (Teaching) Benchmark Statement http://www.qaa.ac.uk/publications/information-and-guidance/publication?PubID=3050#.V_4P0_krIdU.

Society of Authors EC Study of Author’s Remuneration (2015) www.societyofauthors.org

- Log in to post comments