3. Creative Writing and Employment

By Professor Steve May, Bath Spa University

In 2004 I became Subject Leader for Creative Writing at Bath Spa University, and in 2008 Head of Department. At that time our employability performance was poor.

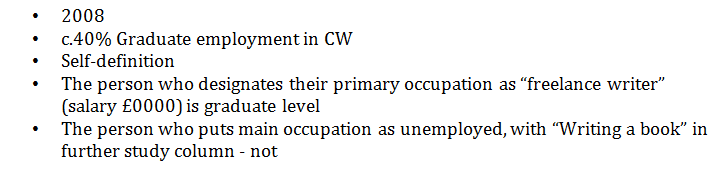

In 2008 DLHE BSU CW showed around 40% of graduates in Professional level employment (incidentally, English performed slightly better). When I analysed the figures it became clear that the respondent’s own definition of what they were doing had significant impact on the results. One person, who designates their primary occupation as “freelance writer” (salary £0000) is graduate level. The person who puts their main occupation as unemployed, with “Writing a book” in the further study column, is not classed as in professional level employment, although the difference between their situations is apparently more perceptual than actual.

In 2009, after some thought and intervention, BSU CW Professional level employment had shot up to 65% (far outstripping English). A good proportion (but not all – we’ll touch on this in a moment) of the improvement could be attributed to changes in self-definition. Some might put this down to cynical manipulation, but I would argue to the contrary: our graduates’ self-image, how they view and define themselves, does have, in my opinion, large impact on their employment prospects.

I carried out a research project for the late lamented English Subject Centre around this time, where I visited a variety of institutions, and talked to CW students about their expectations, fears, and experiences of the subject (see here). One of the key themes was lack of confidence in telling people what they studied, and lack of a clear sense of subject identity.

“Confidence” crops up again and again – often as something that Creative Writing courses give to students, but equally as something that students lack, both in themselves and in Creative Writing as a degree course: “I would have to agree that people seem to almost look down on Creative Writing – I know people who call it the ‘Mickey Mouse’ part of my degree” (Year 2 student). So, as well as cynical manipulation, we began to work on ways to give our CW students confidence, both in themselves, and in the subject. (By “we” here I mean the team at BSU, but particularly Dr Mimi Thebo, who worked closely with me on the curriculum innovations I’m going to mention).

We began with two level five modules, Towards Publication (where students identified and researched target publications, found out what those publications wanted, and made initial approaches to editors etc.) and Into Print (where they actually submitted materials). These innovations evoked much opposition especially from those involved with our postgraduate CW programmes. They feared that our hapless and useless UG students would poison the waters for our stately MA students. We went ahead anyway, assuring them and ourselves that the very nature of the modules meant that students would identify suitable and achievable targets, and would not be pestering Viking and Random house. By and large these modules were successful, something like 80% of students on Into Print getting into Print. Not usually in high paying high profile publications; rather in Cat Monthly, or Fisherman’s gazette. On websites, entering competitions. But the key was getting “out there”, getting the work out there, and experiencing what it is to write and to sell writing.

Our changes in the curriculum are exemplified in our Creative Enterprise module. Designed for level 6 students, this module was initially very hard to get validated, for a variety of reasons. It challenged students to identify some kind of project outside the university, to plan it and to carry it out. The project could be of any kind, not necessarily or even usually directly related to CW as a subject. The project did not need to start and finish within the normal assessment calendar. The assessment was simply a project report, with supporting materials where appropriate. To give a flavor of the module: if a student proposed to write a play, they would be diverted to a script dissertation module. However, if they planned to organize a performance of their play, including casting, finding a director, venue, marketing etc, then that could be an Enterprise project. Other notable projects included the organization of a European fussball tournament, the making of promotional films for charities, and design of a range of swimwear.

The pattern of achievement for the module was very different from the normal bell curve. Put simply, students either did very well, or appallingly badly. This is not a module where you could coast and just do enough to get by. Certainly, we learned as we went along, about the kind of support needed to minimize the appalling, and to make sure students understood the level of commitment required.

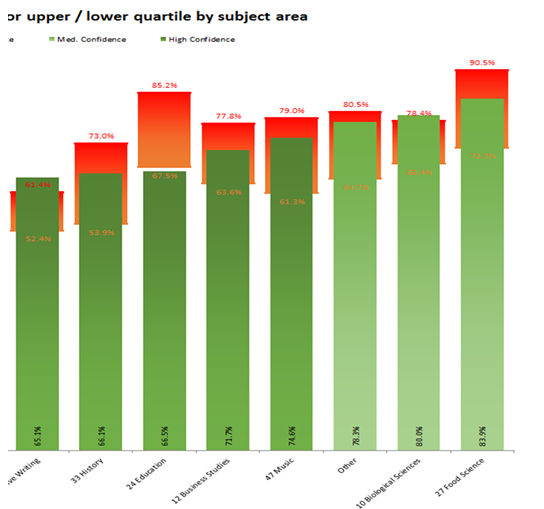

I’ve included a graph below showing an analysis of the recently released latest DLHE figures for subjects at BSU. Creative Writing is a respectable 8th in the university with graduate employment (by the Sunday Times measure) of 65.1% (up from 57.6% the previous year). The sector Creative Writing performance is represented by the red block, and shows an upper quartile of 61.4, and lower of 52.4. It’s interesting to look at these figures (not on graph) for English (74 – 58) and Art and Design (70 – 56). In other words, while I can modestly but proudly point to the BSU better than sector CW performance, it is also salutary to note that the sector CW performance lags horribly behind English and Art and Design.

One example of self-perception, coupled with the kind of outward facing curriculum we introduced. A graduate contacted me, in despair because he couldn’t get even interviews for jobs. When I looked at his cv, he emphasized his work in a garden centre, and made only minimal mention of the enterprising activities he’d taken part in on the course. I suggested he put the fact that he had acted as assistant to the artistic director of the Bath Literature festival at the top of his cv, spelling out the fact that he had had to liaise with writers, meet and greet them, ensure venues were set up as required, and carry out innumerable other duties.

He got an interview with his next application (to a local newspaper – of course post hoc doesn’t equal propter hoc), and although he was not deemed experienced enough for the advertised post, a role was created for him. Of course, he was delighted, I was delighted, our DLHE figures were enhanced – a triple win situation. However, this is not entirely a happy ending.

About a year later the same graduate contacted me, and confided that he really hated the job as reporter on the local paper. I gave him the best advice I could, which was, to decide what he did want to do, to make as many contacts in that area as possible while still trying to stick the hated job for a couple of years. He’s now a Marketing and Communications officer for an FE College. I know because I was notified via Linkedin. Does he like or even love the new job? I don’t know, because he hasn’t told me.

What this case study does emphasise is that the DLHE measure (what graduates are doing 6 months after graduation) is extremely limited. Hence in principle we should welcome the new LEO (Longitudinal Educational Outcomes) data, which “links actual HMRC data to education records, and enables us to understand the salaries of graduates by both subject and institution at multiple points after graduation.” (WONKHE).

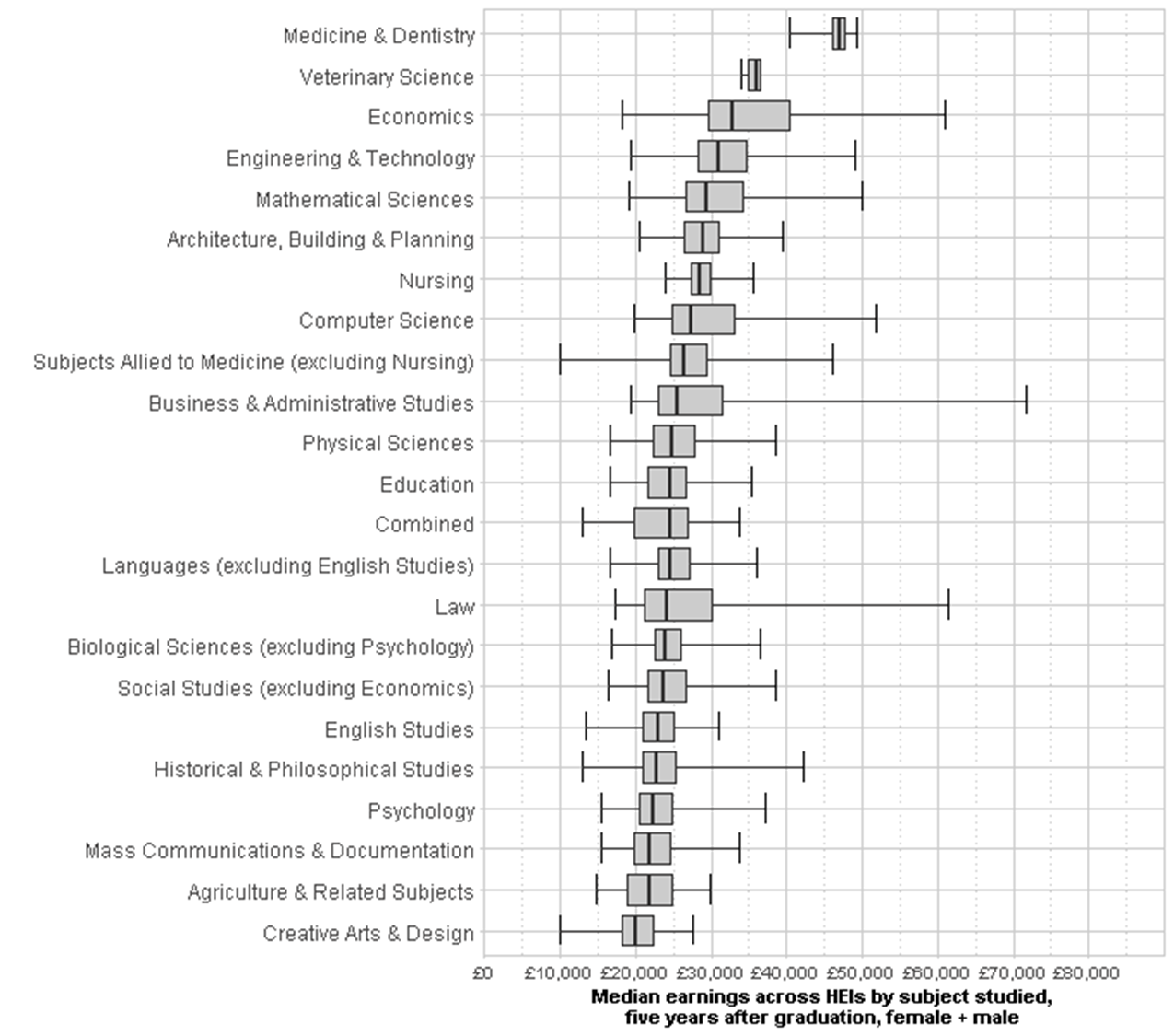

The first release “includes employment and earnings outcomes in 2014-15 for those who graduated in 2009, 2011 and 2013, broken down into 23 subject areas, and split by gender and institution.” The first graph shows median earnings according to subject studied across all HEIs five years after graduation.

Unfortunately we don’t (yet) have enough granulation to see CW on its own, it will either be included in “Creative Arts” or “English” (though given the sector performance of CW in our earlier slide, we might be tempted to assume that CW is probably dragging its cognate subjects downward, rather than the other way round). Creative Arts is clearly bottom of this table, even below the shepherds and shepherdesses of Agriculture and Related subjects. English is a little better (6th from bottom), very close to History, and a little better than Psychology. At the top – and a very clear top, not even overlapping with their nearest rivals, are the dentists and presumably doctors (“medicine”).

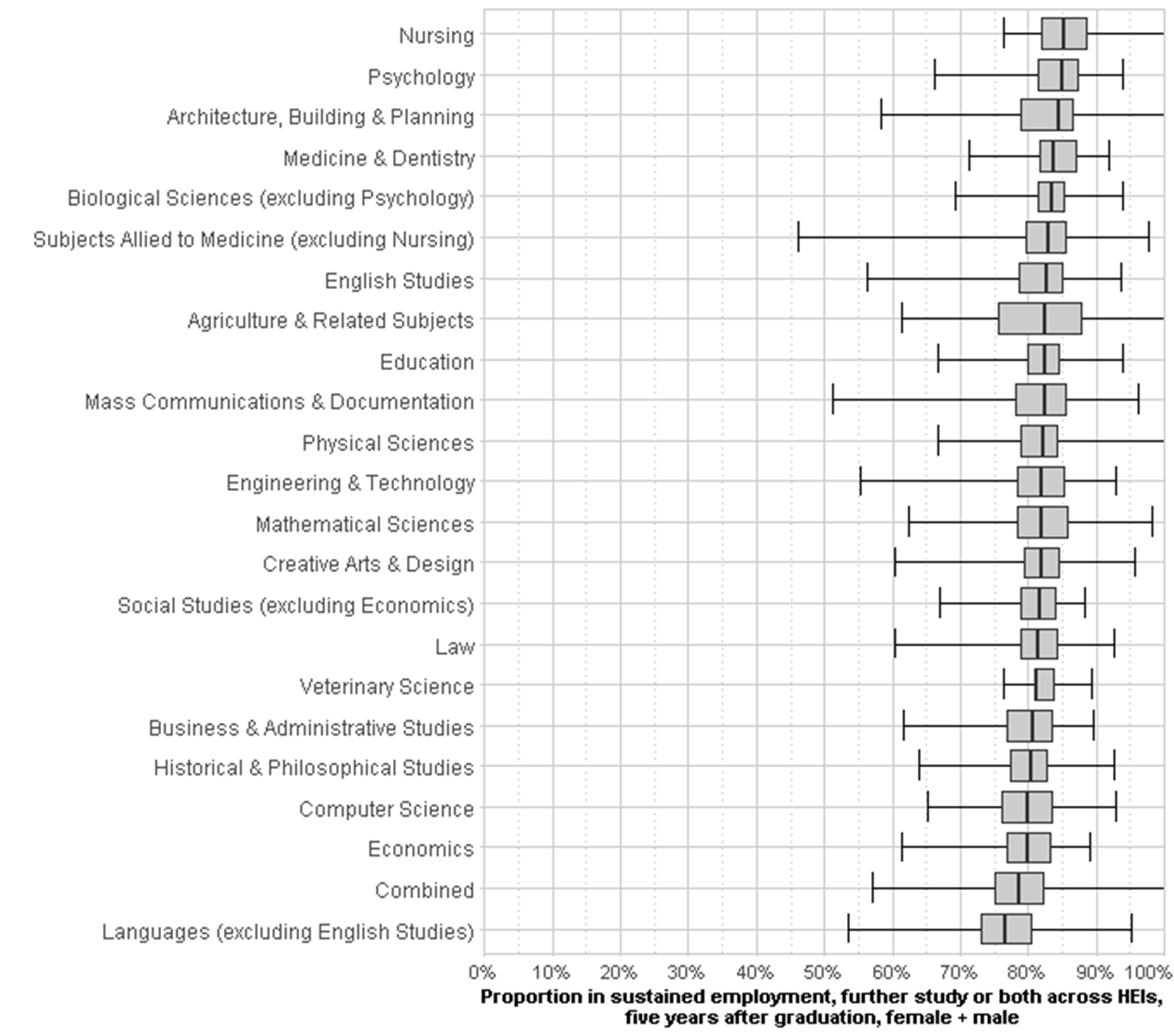

This second graph is harder to analyse. It shows the proportion of graduates in “sustained employment” five years after graduation. At first sight this might give some insight into the oft-cited phenomenon of the “portfolio career” and freelance employment. However, the definition doesn’t quite seem fit for that purpose: “Graduates are considered to be in sustained employment if they were employed for at least one day for five out of the six months between October and March of the tax year in question.” With that caveat, the results are at least intriguing. Dentists have dropped off the top – presumably because given their obscenely inflated incomes they don’t need to work much. Nurses, those hard working servants of society doing useful things are right at the top. And English Studies graduates have hauled themselves into seventh place. Creative Arts, the home of the freelance portfolio career, which we might intuitively expect to see at the bottom of the pile again, is in fact in an almost respectable mid-table.

We need to continue to make our teachers and our students aware of the positive things that a graduate learns from a CW course. We need to give our graduates the ability to make informed choices. And perhaps we should campaign for future tables, league tables, and data collections to include elements other than money and job status. As BSU’s deputy vice chancellor has argued in the THE: “This is the challenge that universities now face: to develop a discourse that is not grounded in short-termism and instrumentalism but in aspiration and the values that might hold us together rather than force us apart.”

- Log in to post comments

.PNG)