4. Occupations of Postgraduate Creative Writing Students

Dr Derek Neale, The Open University

In this presentation I will talk specifically about postgraduate life – before and after a Masters in Creative Writing, and before, during and after a PhD in Creative Writing.

I’m going to offer some anecdotal illustration. These are experiences of students; some of the experiences and jobs have been my own.

I will concentrate perhaps more on writing residencies and what they might consist of. Such residencies might seem odd at first sight. But they are part of a postgraduate’s, a working writer’s, landscape. And they are also perhaps connected to something I’ve previously suggested. Some residencies are, or can be seen as, examples of ‘social entrepreneurship’.

As mentioned in the online update to my Unicamp presentation - social entrepreneurship has risen to greater prominence in the past few years (though its definition tends to be unstable and to cover a wide range of possibilities – indeed this presentation might further stretch the range of definitions). Is Mark Walberg a social entrepreneur? Is Bill Gates? This discussion will be distinctly lower profile in its focus.

Many of the initiatives and commissions that fit into a writer’s portfolio of work might fall under the heading of social entrepreneurship – including writing residencies in care homes, with refugees and asylum seekers, or with other sections of the community. These are roles, often set up in collaboration with existing bodies – funding bodies but also charities and the voluntary sector.

Postgraduate Creative Writing students typically (though not exclusively) have had previous lives outside of academia, and have possibly even had a profitable careers. They are geared for change, possibly of career or maybe they just want to capitalise on their experience of life so far – including their previous work experience – or they perhaps want even to augment that experience.

I came to do my MA in my mid-thirties having had too many jobs to catalogue. In my MA cohort at UEA there was a minority of students coming straight from their first degree but the majority were older – there were two BBC radio/TV producers, a teacher or two, a copy writer, some self-employed PR freelancers – some of whom earned a considerable sum from their first careers (and could continue to do so on a freelance basis). There were also some like me with ragged, zig-zagging job histories.

Jen Webb, Professor of Creative Practice at Canberra University in Australia, claims in her article ‘Writing and the Global Economy’ (https://www.nawe.co.uk/DB/current-wie-edition/editions/international-issue.html ) in the most recent issue of Writing in Education that creative writing students are not perturbed by earning less than their fellow graduates, those from other disciplines; she suggests they would prefer to drive cabs, say, or work in hospitality and retail because their ambition is to earn enough money to sustain their practice. This is true of some certainly at undergraduate level and probably also true at postgraduate level – to an extent.

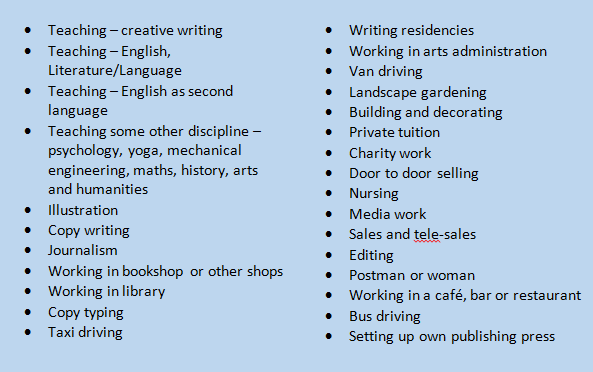

I mentioned in Brazil the inconvenience of a writing career in that it does not exactly pay the rent – far from it - even when the writer is relatively successful. Hence there is a need for portfolio careers – even at postgraduate level, with relatively successful writers. The following are some of the jobs that fit with the postgraduate writing student – before, during and after study. In some cases these jobs will dominate and supersede the writing, not only in terms of income generation but also in terms of time:

Surprisingly – the above list covers the work that postgraduate students – many known to me – have engaged in before, during and after their Creative Writing MA and/or their PhD. I will now concentrate on just one of those possibilities for a moment – writing residencies.

We have recently launched an MA in creative writing at the OU and in that MA we have a strand called Writer in the World – a strand that considers the realities of the routes to publication and performance of students’ work but also what might happen after the MA programme has finished. One writer we interviewed for this strand – to give the students an exemplar - was Tania Hershman, a short story writer and poet. She was interviewed by my colleague Sally O’Reilly about her career and her ways of communicating with the world, in particular her blogging but also her work on writing residencies.

Hershman got her first writing residency in the Science faculty in Bristol University – just by asking if she could do it. See http://www.bris.ac.uk/changingperspectives/projects/writingthelab/

Residencies are typified by having a fixed duration and are located with different kinds of communities. When Hershman came to writing fiction she already had a career – she was a science journalist– and she aimed to combine and augment her interests in science with this residency. She was still intent on learning. She in effect created the residency – by asking to do it. Initially there was no money involved; the faculty had no budget for such a residency. But eventually she got Arts Council funding for a collection of stories based on the residency.

She later got other residencies, in Gladstone’s library, Chester, for instance, and she plans others. But Hershman insists that it is preferable to seek out best possible placements rather than waiting for the highly competitive advertised residencies. She declares that her first two residencies were ‘one way’, in that her writing became the main beneficiary – though some members of each community benefited from discussing their occupations. In other residencies the consequence will not just be writer outputs but there can be workshops and in effect creative writing facilitation and therefore benefits for, and outputs coming from, the community with whom the writer is resident.

I recently examined a PhD by publications which was based on books and experiences arising from a writing residency in a prison, which was originally funded by the Arts Council. This reminded me of when I’d just completed my MA – a friend of a friend of a friend invited me to facilitate writing activities in a prison. This was something I’d long thought about doing and wanted to do – but I can’t now recall the train of thought. This was unofficial, with no Arts Council funding – on each visit I was supposed to be teaching business studies or something similar, but the education officer at the prison was enlightened and smuggled me in under the cover if various headings. I got paid an hourly teacher’s rate and after several months three inmates produced an anthology of their work – Prose from Cons. In effect this was a residency – and it went on for a further 18 months, and produced another collection of prisoner’s writing - The Write Mode. These outputs were the prisoners’ writing and not mine – and for many of them it was the first time they had used a computer or typed anything, or completed any such creative work.

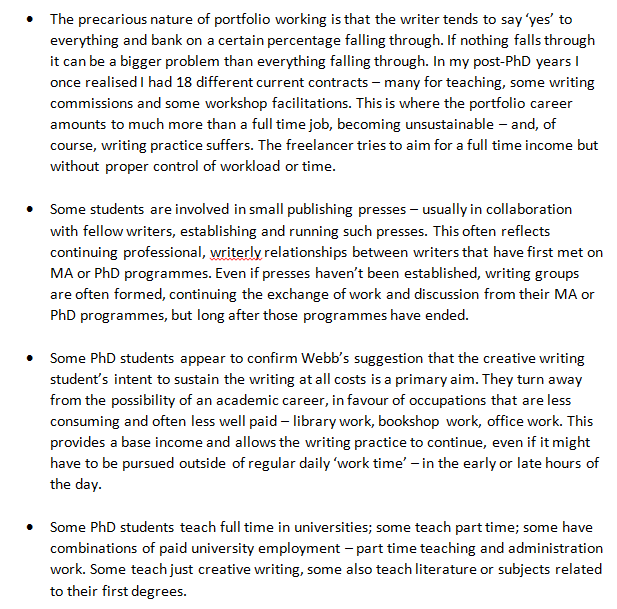

At PhD level I’ve come across various creative writing students with different kinds of portfolio career – many teach, but that can come with its own problems and too much marking at critical points.

Many Creative Writing PhD students at some point or other have engaged, or will engage, in writing residencies. Some such residencies might be termed ‘pure’ writing residencies such as the Hawthornden Castle Fellowship (http://www.writersservices.com/reference/hawthornden-castle-fellowship ), which intends primarily to facilitate the writer’s practice, providing space and subsistence for a set duration of time. These are similar to Hershman’s residencies in the Science faculty and Gladstone Library. But some of the residencies work in more of a two-way fashion and have a social dimension.

This social dimension is exemplified with prison residencies but also there can be residencies with refugees, in care homes, in football clubs, in rural residence for people with learning disabilities, with the London Tube’s Central Line, with BBC World Service, with Radio 4, with a hospital, with a specific ward within a hospital. Some are specifically related to urban locations, old mill towns or deprived inner city areas. Some of these mentioned residencies find the funding themselves, often there are other funding agencies and collaborations, often with a range of art, community and charity organisations, such as local and national writing centres, Tate Modern, Age Concern, Exyzt, CSV, Creative People and Places Network, Social Housing Arts Network, Guild HQ, Arc (Arts and wellbing charity), arts and literature festivals, schools, libraries and museums. These are just example collaborators; there are many more possibilities.

The National Association of Writers in Education has a database of residencies, with cases studies and guidance on applying and establishing new residencies, and a fuller explanation of what writing residencies are or can be, see - www.nawe.co.uk/Private/28398/Live/writing%20residencies%20briefing.pdf - As Hershman suggests, some residences are created rather than applied for. Some projects involve collaborations with other artists – visual or textual artists or musicians – as well as with non-funding art, community and charity organisations.

Is this typical Creative Writing student employment – typical of post MA or in-PhD occupation? It’s difficult to say. On odd occasions such activity does attract AHRC – higher education research – funding. But the fit with typical HE occupations or PG ‘professional destination’ occupations or academic research activity is not easy. There is often a better fit with a teaching or facilitating rather than a research profile. But it is relatively plain to see from these activities how such projects could be perceived positively as ‘social engagement’ and how they might be termed as social entrepreneurship (especially when the writer has initiated and in effect created the collaboration).

Other Creative Writing postgraduate students get Royal Literary Fund fellowships – these are residencies whereby the writer spends typically one day a week at a university in a formulaic manner, advising students usually on their essay-writing or English-language skills. In this way not all residencies will be creative or stimulating for the writer, or productive in terms of leading to tangible community outputs – though improved narrative and writing skills for university students would be considered by many to be a tangible output.

The residency activities undertaken by Hershman and the above mentioned possible scenarios and collaborations fit with the evolving definitions of social entrepreneurship, in that there isn’t a single profit-goal as there might be with the conventional entrepreneur. There is a set of broad social, cultural or environmental goals, associated with the voluntary sector – typically but not exclusively in areas such as deprivation, health care, education and community development.

Profit making isn’t an end in itself – although obviously there is a core requirement of income generation for the writer or social entrepreneur – but that often doesn’t come first in the establishment or initiation of the project.

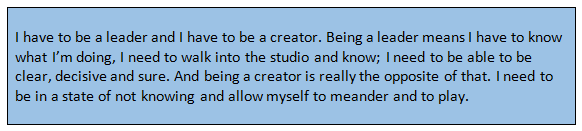

I think this tallies strangely with something the choreographer Crystal Pite said recently (BBC Radio 4 25.7.17 http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b08zxdwx ), when she talked of her process in creating the dance Flight Patterns with the Royal Ballet – the dance was based on the international refugee crisis, and was a project of social engagement.

She said about her role as choreographer –

It seems to me that this is the perpetual state of the creative writer in the world of employment– it echoes their own creative process, but also the dilemma they face when being put into facilitating situations such as teaching, residency collaborations or project leadership.

They are, or have to be, accustomed to both: to lead, to know what they’re doing, but also to be in a state of not-knowing. Writing students are very familiar with uncertainty, and yet also used to directing and controlling words and narratives at a macro and micro level. (see, for instance, my article on this: ‘Being in Uncertainty’ listed below). They can play and initiate, yet they can organize too. And this difficult combination is in demand. I think it amounts to a considerable entrepreneurial strength. Yet it probably doesn’t register clearly on any government statistics or in any destination salary charts.

References

Gladstone’s library - https://www.gladstoneslibrary.org/

Hawthornden Castle Writing Fellowship – this accepts only traditional, letter applications; there is no website. These are the details as per the Writers Services website http://www.writersservices.com/reference/hawthornden-castle-fellowship

Tania Hershman – recorded interview with Sally O’Reilly, not published or broadcast. Open University course materials. August 2017.

Tania Hershman (and Prof. Paul Martin) – writing residency in Bristol University Science Faculty http://www.bris.ac.uk/changingperspectives/projects/writingthelab/ (accessed 01.08.17)

Tania Hershman – website http://www.taniahershman.com/wp/ (accessed 01.08.17)

Charles Leadbeater, The Rise of the Social Entrepreneur, Demos, 1996.

Joanna Mair, Jeffrey Robinson, and Kai Hockerts, Social Entrepreneurship, Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

NAWE (National Association of Writers in Education) database of, and information about, writing residencies www.nawe.co.uk/Private/28398/Live/writing%20residencies%20briefing.pdf

Derek Neale, ‘Being in Uncertainties, Mysteries and Doubts: Negative Capability and the Place of the Imagination in the Academy Today’ in Writing in Education Issue 56 Spring 2012 https://oro.open.ac.uk/30858/

Crystal Pite, BBC Radio 4 25.7.17 http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b08zxdwx

David Swann, The Privilege of Rain Waterloo Press 2010.

Jen Webb, ‘Writing and the Global Economy’ in Writing in Education Issue 72, Summer 2017 (https://www.nawe.co.uk/DB/current-wie-edition/editions/international-issue.html )

- Log in to post comments