1a. Literary Tourism and Literary Heritage Sites (in English)

Nicola J Watson, Professor of English Literature, Open University

The Impact of Literary Research Outside Academia

Today I am going to address our core workshop questions –

>> how existing and emerging directions of literary research make an impact outside academia

>> how this impact could be cultivated further

>> how literary research programmes in the academy help serve employability and skills-needs outside academia

>> to what extent literary research is suited to collaborate with businesses and public organizations for the public good

>> and what emerging areas of literary research facilitate the above…

through considering the existing and emergent relation between literary study and research within academia and the development of literary tourism and literary heritage sites. I’ll speak for about thirty minutes, concentrating primarily on the UK, but I’ll also be referring out to some European examples.

My own expertise in this area derives from my past research into the history of the phenomenon of literary tourism, that is to say, the practice of visiting places associated with authors and their works. I was interested in when this desire arose, why, and what forms it took, and as a result I wrote a book, The Literary Tourist: Readers and Places in Romantic and Victorian Britain (2006), focussing on the first moments that tourism to different sorts of literary places became commercially significant. I looked at the rise and shaping of interest in the writer’s grave, in the writer’s birthplace, in the places where they had lived and worked, and in places which they had written about and reimagined. My examples included Shakespeare, Burns, Scott, the Brontës, Hardy, and children’s literature. I examined how these places were experienced and memorialised, and increasingly at how they were remade to correspond more closely to the literary text.

Out of this came further publications on literary tourism and travel-writing, including a conference and an edited collection (Literary Tourism and Nineteenth-century Culture 2009), and essays on the invention of Shakespeare’s Verona, the craze for Shakespeare garden, the invention of Shakespeare’s Stratford-upon-Avon, the development of tourism around sites associated with Charles Dickens, Jane Austen and Jean Jacques Rousseau.

I am presently working on a book more focused on literary place-making than literary tourism per se, entitled The Author’s Effects: A Poetics of the Writer’s House Museum. This looks at the emergence of the writer’s house museum as a genre of life-writing. My examples here are drawn from Britain (Shakespeare, Burns, Scott, Wordsworth, Keats, Byron, Dickens, the Brontës), Europe (Petrarch, Tasso, Rousseau, Chateaubriand, de Staël, Dumas, Victor Hugo), and North America (Emerson, Thoreau, Hawthorne, Alcott, Dickinson, Twain, Hemingway).

One of the results of working on these academic projects is that I have been involved in

>> public speaking at literary festivals, festivals of ideas, and to literary societies

>> a number of projects large and small both in Britain and Europe concerned with literary tourism and heritage sites. These range from the academic-led to consultancy for tourist boards, archives and museums. They comprise developing pure academic study and understanding of literary and screen tourism, and of literary heritage properties; developing public engagement through academic-led online exhibition; developing literary tourist sensibility in the public through academic consultancy; and developing literary tourism/writer’s houses.

I will talk at more length about some of these and other projects that I have been more peripherally involved in later, but before I do, I want to briefly remark upon the pressure on the academy to make literary research have impact outside the academy.

The ‘impact’ agenda for research in the UK and Europe more generally is being driven by public policy. It is designed to transfer academic expertise more readily and rapidly beyond the university, and to make it more immediately profitable. The policy aims not just to transfer knowledge more efficiently from the academy to employment and enterprise outside academia, but also, effectively, to transfer the benefits of public funded research to both public and private spheres beyond academia. Arts research is therefore increasingly funded upon a model derived from the sciences, and funded if it ‘solves’ perceived problems. In its instrumentalising ambitions, the ‘impact agenda’ is congruent with the ‘employability’ agenda, which seeks to make university education more like a training programme for the future work-force.

As literary tourism and heritage are underfunded and understaffed areas within the economy, academics and universities are increasingly recruited (and recruit themselves) as research and development departments with guaranteed impact. As the list of projects I have just cited suggests, this is working especially well at present in Scotland, where the politics of nationalism work powerfully both in the universities and the nation at large to promote the study of heritage and heritage tourism.

Literary Tourism and Heritage Studies Programmes in the UK

Let me begin with surveying tourism and heritage studies programme in the UK which are relevant to, or focused on literary studies. There are, in fact, hardly any. While there are tourism, heritage, gallery and museum studies programmes at both undergraduate and masters’ level, few pay much attention to literary tourism. If they do, this tends to be associated with research strengths among faculty in the area, which has become recognisable as a field over the last ten years or so, and the interest is often supported by Research Centres. It is very frequently the case that interest in literary tourism within the university is driven by local literary heritage.

For example:

Directions of Research and Collaborations in/beyond the UK

The fundamental form of funded research and research collaborations tends to be to do with solving ‘problems’ set by the funders (primarily British Academy, AHRC, Horizon 2020). These problems tend to be envisaged from the angle of heritage institutions as

>> engaging contemporary culture with the past, and

>> engaging new, younger, and socially and ethnically diverse audiences.

In terms of tourism and heritage, this is typically imagined as ‘adding value’ through enhancing the appreciation and apprehension of the past. This may be expressed through

>> enhancing the experience of place (place-making from built environment through to landscape)

>> giving meaning through narrative to the archive, broadly conceived as encompassing material, visual and sonic culture.

The structure of funded research tends to be collaborative, with an emphasis on collaboration between academia and practitioners; it contains detailed planning for how research will translate into practical public engagement and preferably hard financial advantage for the institutions outside academia. The outcomes of academic research are often re-expressed through creative response by writers/artists.

Looking forward, research in this field is likely to continue to be driven by funding which is likely to follow certain opportunities/interests/trends:

>> Research in this area is likely to become yet more interdisciplinary. It already potentially spans biography, life-writing, literary geography, travel-writing, an interest in the relations between ‘literature’ and material/visual/sonic culture, an interest in authorial celebrity, reception, screen and other adaptation, transmediation, forgetting and commemoration, an interest in the representation of place and object, interest in loco-specific writing (eg inscription, epitaph etc), in the personal essay, in the history of emotion, in place-making and architecture. However, it seems likely that in future it will be necessary to collaborate with research conducted through the methodologies of social sciences to become less historicist and more presentist.

>> Research is likely also to become more instrumentalist. Thus it is likely to link to locality (regional and national), anniversaries, and national events (by which I mean, for example, that the British Library exhibition ‘Writing Britain’ was designed to coincide with the 2012 London Olympics). It will collaborate with museums and archives to add value to their collections and engage new audiences. Possible emphases include the history of and contemporary visitor engagement with the place (see for example, ‘The Postcard Project: Placing the Author’ or the theory and practice of how best to display/narrate/relate objects and localities. TRAUM is interested, for example, in how captions ‘work’ to narrate objects, in writer’s house museums as immersive theatre etc; ‘The English Literary Heritage project’ aims to explore new ways of exhibiting literary manuscripts and objects to a wide audience. Other possibilities include harnessing research to underpin the creation of new literary heritage locations to serve a more diverse public, or the strategic addition of new ones to pre-existing tourist sites.

>> Research is showing signs of shifting towards questions of how new technologies have changed the literary tourist experience and how they might be used to inform and enhance it. Thus there is strong interest in the current cultural passion for screen adaptation and immersive experiences which have produced an upsurge in screen tourism and the desire for multi-media experiences such as Warner Brothers Harry Potter World. There is interest in exploring ways of displaying place using various types of technology from the mobile phone through to the online environment, and interest especially in the possibilities of interactive technology from the mere dressing-up box to engaging the public online as citizen researchers in their own rights

>> BUT, rather paradoxically, academic research in the area is likely to become more self-defensive against the democratisation of knowledge made possible by the digitisation of so much of the archive and its dissemination on the net. This means that academic skills in navigating the archive are increasingly being turned to elements of the archive that can’t be adequately or fully digitised – objects so far of no value or interest languishing in vaults, the backs and edges of places and objects that have escaped visual representation, the interest in theorising the smell and feel of objects etc.

>> Finally, what literary research brings to tourism and heritage studies is an interest not so much in material culture but in thinking about the immaterial, incorporeal, and imaginary. The whole, peculiar point (and problem) of literary tourism and heritage places is that, really, there is ‘nothing to see’ except for those who can see through the eyes of the imagination.

EXAMPLE 1: ON THE SPOT ENCOUNTERS

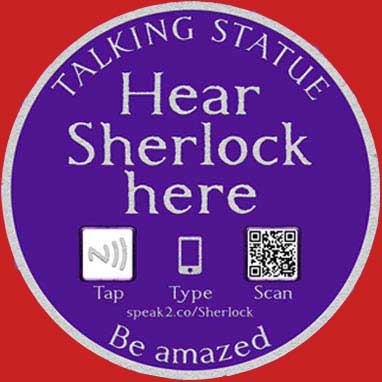

‘Pass a Talking Statue, swipe your phone on a nearby tag and hey presto; your phone rings. And it’s Queen Victoria on the line…or Peter Pan…or Sherlock Holmes’ Talking Statues London: A way of bringing statues back into cultural life for the younger generation in particular in cities in Britain and now USA. It included a competition to write a speech for the statue of Shakespeare in the British Library.

EXAMPLE 2: IN THE ARCHIVE

University of Stirling and British Library, ‘Writing Britain’s Ruins’, 2018

This funded project (led by Prof Dale Townshend) combines academic research into the written representations of ruined abbeys and castles across Britain with a programme of public lectures at Strawberry Hill and an exhibition co-curated with the British Library. Outputs include a single-author monograph and a collection of essays published in conjunction with the British Library exhibition.

EXAMPLE 3: PERFORMANCE EVENT

The Garrick Ode, 2016. Re-staging (under the auspices of the University of Birmingham) for the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death of the occasion in 1769 when Britain’s most celebrated actor-manager David Garrick staged the Shakespeare Jubilee in Stratford-upon-Avon complete with an Ode backed by full orchestra and in so doing inaugurated and invented modern practices of the annual commemoration of Shakespeare’s Birthday.

EXAMPLE 4: ONLINE RESOURCE

RÊVE (Romantic Europe: The Virtual Exhibition), launching July 2017

A virtual exhibition of romantic objects, artefacts and landscapes drawn from across European Romanticisms bearing on the themes of romantic authorship and romantic textuality as part of an academic investigation into cross-border, cross-period interconnections between European Romanticisms, and with a view to building pedagogical and public engagement with these places and objects. Co-ordinated and curated by Watson.

EXAMPLE 5: HERITAGE SITE

Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, redeveloping Shakespeare’s ‘New Place’, 2016

This project started with the opportunity of the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, and a problem – New Place itself was demolished in the late eighteenth-century, and although the site had been successively occupied by a small theatre and a series of commemorative gardens, it was in a sense ‘empty’. The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust decided to redevelop the site, and as part of that design process asked me (amongst others) to come and consult with them on the meanings of houses/places associated with writers, on what constituted the bare grammar of a writer’s house museum, and very specifically on the meanings of writer’s desks and chairs and Shakespeare’s chair and desk in particular. The site is now re-described primarily as ‘a ground of inspiration.’

Bearing of the Above on Employment and Enterprise

EMPLOYMENT:

In practice, as a result of funded research projects the interface between academia and institutions such as museums, archives, galleries, and heritage conservation is steadily growing more porous. Projects are increasingly placing doctoral and post-doctoral students as interns into a variety of tourism and heritage contexts, supplying them with experience and contacts. See for example, this studentship recently advertised at the University of Glasgow doctoral student:

ENTERPRISE:

Many researchers are successfully instrumentalising their own work as freelance public intellectuals in the ways I have been describing. However, two health warnings are in order. The first is that on the whole this enterprise is not paid, at least directly. Some have found ways of being paid, but much of this work might be said to be unpaid (although this is a controversial statement, as academic salaries are publically funded). Moreover, as academics are increasingly no longer gatekeepers to the archive after mass-digitisation, there is much competition from leisured and often well-informed private intellectual enterprise. See, for example, this website offering a guide to the history of writing about a famous tourist site, Poole’s Cavern. It provides 25 carefully chosen extracts taken from a total of 9 antiquarian books.

And secondly, it proves very difficult to sell our traditional stock-in-trade – the fruits of careful critical reflection. The public are much more enthusiastic about sentiment than scepticism.

- Log in to post comments

.PNG)