You are here

- Home

- Music, Moral Management, and Mental Health: What can we learn from the Victorians?

Music, Moral Management, and Mental Health: What can we learn from the Victorians?

This article is written by Dr Rosemary Golding, Staff Tutor and Senior Lecturer in Music, based in the School of Arts and Humanities at The Open University. It is written for the OU's 'Arts and Humanities Research in a Time of COVID-19' online series and published on 8 June, 2020.

Towards the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic period, I reflected on my own blog about the ways in which music had been used in the past to alleviate the kinds of loneliness, social isolation and fragile mental health that many of us were feeling. Music has continued to be an important part of the ways in which we’ve adapted to the lockdown, with communities gathering in a distanced or virtual way for singing and dancing. Many professional and amateur musicians have provided solace and entertainment with new video technology featuring hundreds of singers and instrumentalists, or individuals taking multiple parts. Technology has been key to bridging the airwaves, but the shared experience and love of music – whether performing or listening – has proved an important factor in offering social and cultural opportunities. For others, however, the essential features of musical performance also require physical proximity, real-time interaction, and the relationship of performer and audience that cannot be reproduced with today’s technology.

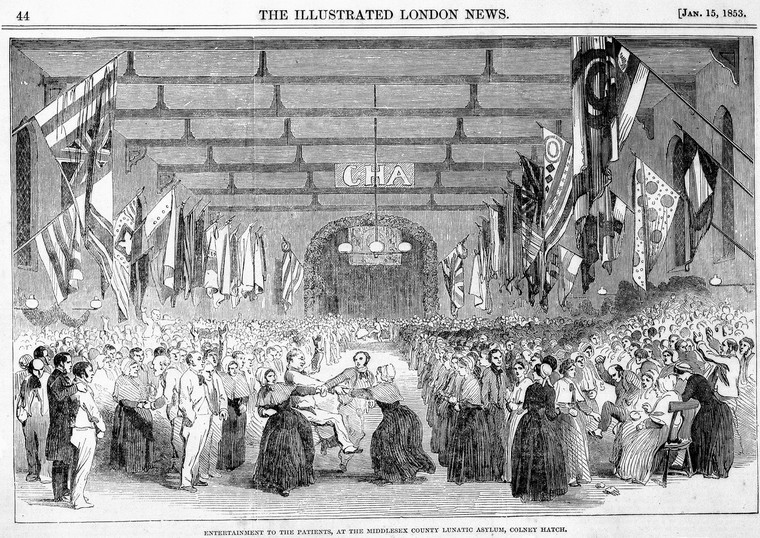

My own research into the use and experience of music in nineteenth-century lunatic asylums shows how music has been adapted in another context for the benefit of patients removed from their usual surroundings. During the nineteenth century, medical officers made the case for music’s role in alleviating boredom and monotony, offering social opportunities, promoting physical exercise through dancing, allowing for personal expression and connecting patients to the familiar sights and sounds of the outside world. Music was included as part of a larger scheme known as ‘moral management’, which gradually replaced physical methods of restraint and treatment. In the absence of much medical understanding of mental health, doctors dealing with psychiatric patients developed systems aimed to control their lives as carefully as possible, on the one hand wanting to offer comfort, homeliness and familiarity, and on the other seeking to restrict excitement, strong emotions or sudden changes. William A.F. Browne, writing in 1837, summarised the system of moral management as ‘kindness and occupation’ [p. 177]. Asylums were managed with strict timetables, patients were engaged in work either outdoors or around the institution, diet and clothing were carefully controlled. Proponents of moral management recommended patients were offered outside exercise, their surroundings were well-furnished and decorated, and they were kept busy and occupied with games, reading, and other recreational activities including dancing and music.

Image: Entertainment to the patients at the Middlesex County Lunatic Asylum, Colney Hatch, Wellcome Library.

How does the practice of moral management compare with the ways in which we can maintain our own mental health during the ongoing pressures and changes of 2020?

Central to the idea of moral management was a regular structure and routine, allowing space and time for the elements of sleeping, eating, working and recreation during each day. Patients in the nineteenth-century asylums were brought into this regular rhythm both as a means of helping them develop self-control, and as a part of rehabilitation, echoing the living and working practices they would resume on return to the outside world. The physician John Conolly repeatedly used the word ‘order’ to describe the asylum he managed at Hanwell, north London, in an 1856 volume. In an 1842 Report, Conolly noted ‘The impression produced on patients newly admitted to the asylum is… strongly indicative of the general character of the place being favourable to curative endeavours. Their wildness and irregularities often rapidly subside, and their habits conform to the general order and the decorous routine so remarkable in the majority of their fellow-patients.’ [pp. 241-242] Of course, the effect of COVID-19 has been to shake many elements of our established routines and orders, but new, even temporary, structures like those imposed upon asylum patients can often be beneficial in constructing a feeling of control and stability.

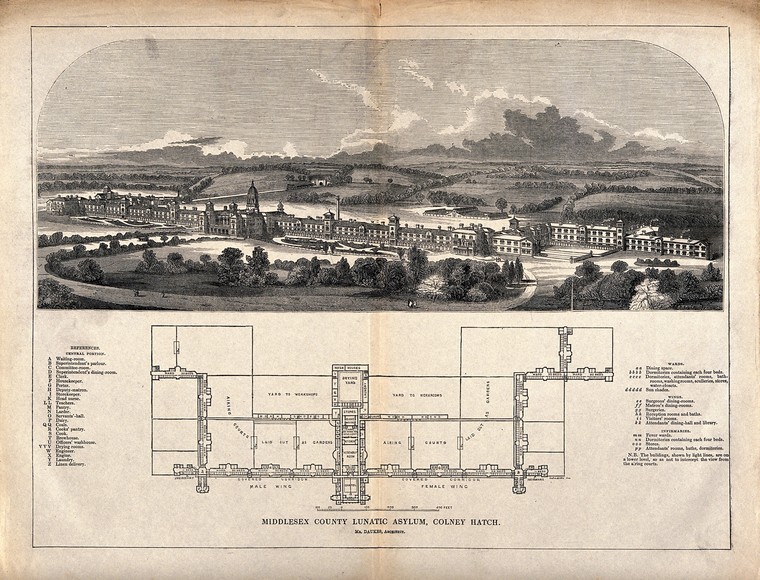

From the early nineteenth century patients were encouraged to work in order to keep occupied, thus moving their minds away from the causes of their mental affliction. Asylums founded after the 1808 Lunacy Act, which gave County authorities the mandate to fund separate institutions for the insane poor, were often built in rural areas with provision for their own farmland. Male patients were frequently given manual employment there, or in workshops according to their trades. Female patients were employed in the garden, kitchen, stores, or in housework. In his 1817 publication, John Haslam recommended ‘bodily labour in the open air, with moderate employment of mind, directed to some useful object’ [p. 15]. However, Haslam also cautioned on the importance of choosing the ‘proper time when employment will become beneficial’, as well as the type of occupation best suited to the patient and his situation: ‘The employment may be that to which he has been accustomed, and to which he will conform by habit – that which delights him, and brings back to his recollection the associations of former and happier days’ [pp. 72-3]

Image: Middlesex County Lunatic Asylum, Colney Hatch, Southgate, Middlesex: bird's eye view with detailed floor plan and key. Wood engraving by Laing after Daukes. Wellcome Library.

In addition to work, which was often outside, asylums were carefully situated in order to maximise the benefits of fresh air and country views. Of course, situating institutions a good distance from urban centres also meant that the new asylums and their patients were distanced from most of the population. Brown recommended that a site chosen for an asylum should be healthy and peaceful, with a varied landscape. He suggested ‘If the building be placed upon the summit or the slope of a rising ground, the advantages are incalculable. To many of those whose intellectual avenues to pleasure are for ever closed, the mere extent of country affords delight; to some the beauty of wood and water, hill and dale, convey grateful impressions; to some the inanimate objects, the changes of season, the activity of industry, the living and moving things which pass across the scene, form a strong and imperishable tie with the world and the friends to which the heart still clings; to others the same objects may remind of freedom, its value, and the price by which it may be purchased’ [p. 182]. Many have found that fresh air and exercise have been essential for maintaining healthy bodies and minds through the current pandemic, but as Browne notes, the associations of location and surroundings are very personal.

Moral management, in theory, struck a balance between imposed structures and the needs of the individual. In practice, as institutions grew, individual treatment was set aside and the need for economical and large-scale practices dominated. Within this context, however, routine, surroundings, occupation and entertainment for mental health remained a priority.

Suggested further reading:

Leonard D. Smith, Cure, Comfort and Safe Custody: Public Lunatic Asylums in Early Nineteenth-century England (London: Leicester University Press, 1999)

Request your prospectus

![]()

Explore our qualifications and courses by requesting one of our prospectuses today.