Snapshot: Dressmakers

Dressmaking stood out as a trade that allowed women to set up their own business from a young age, even compared to other parts of the clothes-making sector.

The trade

The reason for these dynamics can be found in the structure of the trade. Dressmaking required an apprenticeship, after which the individuals could run their own businesses. In mid-nineteenth century, the sector was renowned for its extermely poor working conditions, particularly for the apprentices. Hence, only those desperate to earn wage, such as young and single female were prepared to endure these poor working conditions than others. Historical accounts have documented these working conditions and structures of the sector. However, left examined have been the employers and owners of the dressmaking and milliner shops. These owners were often successful businesswomen, who have received less attention in the historiography on women’s work, which tends to focus.

As a sector, dressmaking increased in importance between 1851 and 1901, driving an expansion of female business opportunities, before numbers started to decline in 1911. The reasons for this decline were complex, and can be found in a combination of the following:

- the availability of sewing machines at home leading to a rise in amateur dressmaking for the family,

- new technology and systems that transformed dressmaking from a craft sector to an increasingly industrialised, factory-based one, and

- the rise of the department store

Milliners and hatmakers, whose artisanl craft could not be so easily mechanised, did not experience a similar drop in numbers in 1911.

Dressmakers in London

Dressmaking was particularly important for women from Russia, Europe and the Middle East, but migrants from all over the world engaged in dressmaking.

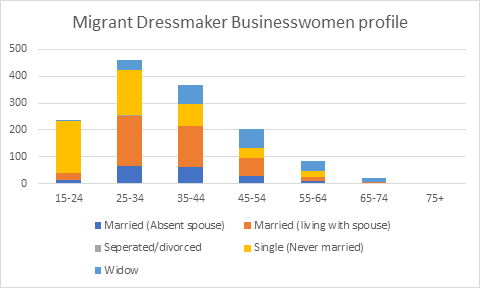

Dressmaking women in London were often young and more likely to be single than for instance laundresses, grocers and shopkeepers.

Dressmakers who married did so at a later age than the average woman. Marriage either enabled women to set up their own business or made it more difficult to work for someone else. Marriage was an enabler as the additional resources of marriage allowed them to set up a business. However, marriage could be also be disabler because it prevented them from committing to the the long working days. of waged employed, which in turn would push married young gwoman into self-employment which was more precarious.

Dressmaking businesses varied. While more affluent businesses were part of London society showrooms, othere much smaller establishments were places where clients brought in their fabrics, or pre-made department store dresses that had to be alter. Since the smaller establishments were likely to be bootstrap enterprises, many young dressmakers set up businesses together as partnerships in order to share these costs.

A career in dressmaking allowed a single woman some independence – 13 percent of single entrepreneur dressmakers were heads of households, while worker dressmakers often depended on others, with only 3 percent heading their own household. This opportunity of an independent life was deemed one of the more compelling reasons to choose a dressmaking apprenticeship over other occupational options, as indicated by the introduction of a contemporary Guide to Trade for Dressmaking, which also mentioned that a dressmaker would be able to have a house of her own.

Get in touch

Contact [email protected]