Is the 2020 New Deal a Green New Deal?

This blog is written by Dr Vicky Johnson. Vicky leads the economics line of study across a range of OU geography modules in relation to the environment. She is part of the team behind the new Open University module, Environmental Policy in an International Context.

The COVID-19 crisis began with a focus on human health, but it wasn’t long before the economic impacts of the imposed lockdowns entered minds. The lockdown measures limited the production of goods, their transportation across the world and consumers' demand for these goods. This was seen across the UK, just like elsewhere across the globe. As the UK government announcements began to focus on steadily falling COVID-related death rates, and lockdown measures began easing, attention turned to the economy. In the UK, the government announced plans to ‘take back control’ of the economy.  As part of this the Prime Minister (pictured right) announced an approach to ‘rebuild Britain’ by powering economic recovery. The headline was very definitely directed on ‘build, build, build’ with substantial infrastructure work being the focus.

As part of this the Prime Minister (pictured right) announced an approach to ‘rebuild Britain’ by powering economic recovery. The headline was very definitely directed on ‘build, build, build’ with substantial infrastructure work being the focus.

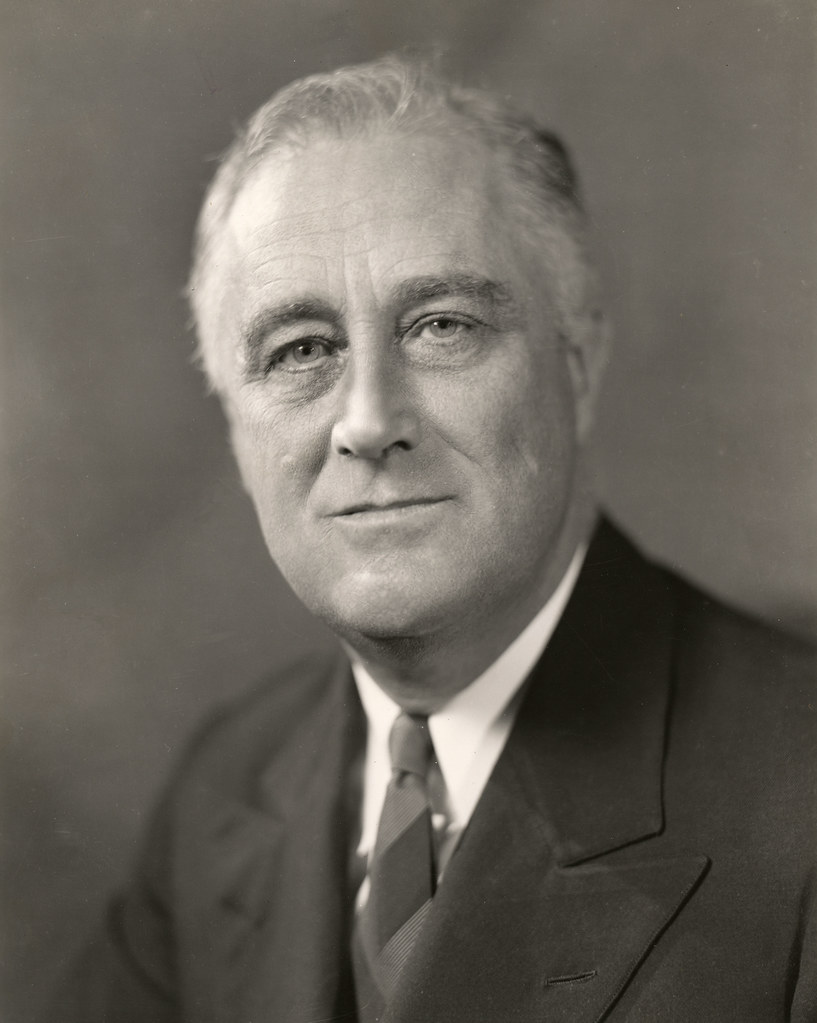

Boris Johnson’s approach can be compared to the 1930's New Deal in the United States (US). In that time and place a government-led programme, based on the Keynesian policy of stimulating economic growth through increased public expenditure, was used. This was introduced by President Franklin Roosevelt (pictured below) following his election in 1933, with a wide range of New Deal measures passed by Congress within the first 100 days of him coming to office. It could be argued that the speed of response to the situation in the UK meets a similar 100 day timeframe, with lockdown beginning on 23 March and the ‘rebuild Britain’ announcement, on 30 June, 100 days later.

The 1930’s US New Deal ran for several years and was successful in meeting its stated objectives of stimulating economic growth, raising employment and lifting the US economy out of recession, as assessed using the economic measures of the time. But it came at an environmental cost as much of the stimulus to the economy resulted in increased consumption of fossil fuels, meaning the New Deal certainly was not an environmentally sustainable model. Although arguably there were green shoots created that can still be seen today, such as the investment in hydroelectric power (HEP) as seen in the Norris Dam in Tennessee (pictured below). Over 80 years later, the dam continues to generate cheap and renewable energy. It is also worth noting that the 1930’s approach is credited with other social gains such as enhanced welfare that remains in place today. The level of investment in the 1930’s New Deal was vast. For several years it equated to between 5% and 7% of the country’s economic output (measured by GDP). The £5 billion announced by Boris Johnson is much, much smaller. Even if this was spent in a single year it would be less than 0.25% of the country’s economic output, so very small in scale compared to President Franklin Roosevelt’s approach ninety years ago.

The 1930’s US New Deal ran for several years and was successful in meeting its stated objectives of stimulating economic growth, raising employment and lifting the US economy out of recession, as assessed using the economic measures of the time. But it came at an environmental cost as much of the stimulus to the economy resulted in increased consumption of fossil fuels, meaning the New Deal certainly was not an environmentally sustainable model. Although arguably there were green shoots created that can still be seen today, such as the investment in hydroelectric power (HEP) as seen in the Norris Dam in Tennessee (pictured below). Over 80 years later, the dam continues to generate cheap and renewable energy. It is also worth noting that the 1930’s approach is credited with other social gains such as enhanced welfare that remains in place today. The level of investment in the 1930’s New Deal was vast. For several years it equated to between 5% and 7% of the country’s economic output (measured by GDP). The £5 billion announced by Boris Johnson is much, much smaller. Even if this was spent in a single year it would be less than 0.25% of the country’s economic output, so very small in scale compared to President Franklin Roosevelt’s approach ninety years ago.

The UK's 2020 New Deal has been promoted as ‘a clean, green recovery’, but is there evidence for this claim? There are some elements that could be classed as ‘green’ using current economic thinking. For example, the inclusion of tree planting (although this was merely a repeat of a pre-COVID promise), funding for cleaner technology and home insulation to reduce emissions. These elements, of both nature conservation and low-carbon energy technologies, can be argued to have the potential to achieve green growth by decoupling carbon emissions, along with other forms of environmental degradation, from economic growth. These activities all connect well to the Keynesian approaches of stimulating aggregate demand, but arguably in a greener way by focusing on environmentally sustainable sectors of the economy. Using this commentary, these elements could be classified as appropriate to a Green, or perhaps only slightly greener, New Deal.

The UK's 2020 New Deal has been promoted as ‘a clean, green recovery’, but is there evidence for this claim? There are some elements that could be classed as ‘green’ using current economic thinking. For example, the inclusion of tree planting (although this was merely a repeat of a pre-COVID promise), funding for cleaner technology and home insulation to reduce emissions. These elements, of both nature conservation and low-carbon energy technologies, can be argued to have the potential to achieve green growth by decoupling carbon emissions, along with other forms of environmental degradation, from economic growth. These activities all connect well to the Keynesian approaches of stimulating aggregate demand, but arguably in a greener way by focusing on environmentally sustainable sectors of the economy. Using this commentary, these elements could be classified as appropriate to a Green, or perhaps only slightly greener, New Deal.

There are elements of the recovery plans that cannot be described as green-at-heart, such as the road projects and lack of focus on green or sustainable approaches in the housing, hospital and education spending plans. Realistically the public expenditure focus would need to go much further to match what many would expect a Green New Deal to look like. This would have a low-carbon economy as central to all the proposals and not just some.

So, whilst there are some elements of greening within Boris Johnson’s New Deal announcement, the focus was clearly on economic growth, using Keynesian economic theory, over and above the environmental and social opportunities. This raises questions as to just how ‘green’ any infrastructure based New Deal can be if economic stimulation is at its core. It is important to remember that the economic approach on which the recovery is being based is the same approach that has led to the current environmental and social problems across the globe. Therefore, it is important to question if this route can really provide a green solution.

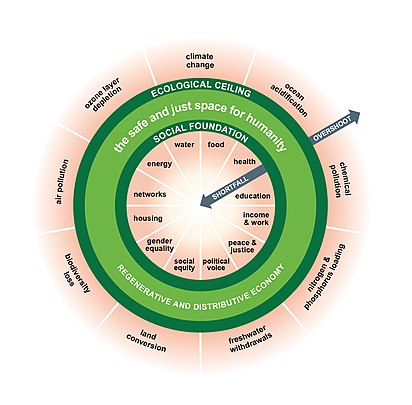

Here, thought should be given to the growing tide of opinion regarding the need for a new, and totally different, economic story. Changing such stories takes time and so, perhaps, it would be too much to expect the current UK government, brought up on and taught the existing economic tale, to make this move now. The alternatives that are thought about and in cases being actioned elsewhere include planetary boundaries, degrowth, steady state economy, circular economy, doughnut economics (as demonstrated in the image on the left), embedded economies and sustainable consumption. In the UK, even if a fully Green New Deal had been proposed it perhaps wouldn’t have gone far enough in moving away from holding the economy central to action. So, although there has been a missed opportunity for Boris Johnson to make the ‘New Deal’ a much ‘Greener New Deal’, this probably wouldn’t have been enough for many. It was probably too much to hope that thinking more creatively about the post-COVID recovery would include exploring totally different models that bring together social, health and environmental elements without the economy at the centre.

Here, thought should be given to the growing tide of opinion regarding the need for a new, and totally different, economic story. Changing such stories takes time and so, perhaps, it would be too much to expect the current UK government, brought up on and taught the existing economic tale, to make this move now. The alternatives that are thought about and in cases being actioned elsewhere include planetary boundaries, degrowth, steady state economy, circular economy, doughnut economics (as demonstrated in the image on the left), embedded economies and sustainable consumption. In the UK, even if a fully Green New Deal had been proposed it perhaps wouldn’t have gone far enough in moving away from holding the economy central to action. So, although there has been a missed opportunity for Boris Johnson to make the ‘New Deal’ a much ‘Greener New Deal’, this probably wouldn’t have been enough for many. It was probably too much to hope that thinking more creatively about the post-COVID recovery would include exploring totally different models that bring together social, health and environmental elements without the economy at the centre.

You can learn more about the alternative ways of thinking in The Open University module ‘Environmental policy in an international context (DD319).

Request your prospectus

![]()

Explore our qualifications and courses by requesting one of our prospectuses today.