Stuck in a pandemic: are international students migrants?

Parvati Raghuram, Professor of Geography and Migration and Dr Gunjan Sondhi, Lecturer in Geography from The Open University write for Open Democracy. This article was originally posted on 11 May, 2020.

For long, international students were not included in most migration debates because they were seen as temporary sojourners. Did things change?

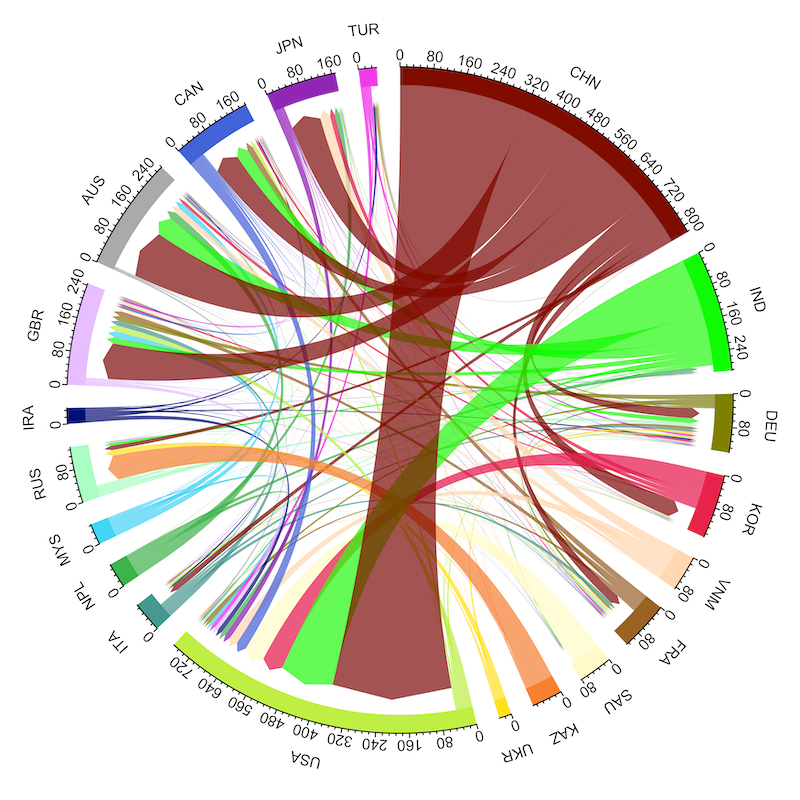

International students are a growing part of the global migrant population. In 2017, there were 5.3 million internationally mobile students according to UNESCO. The top two countries of origin are China and India while the top destinations are the US, Australia and the UK.

For long, international students were not included in most migration debates because they were seen as temporary sojourners, moving for a few months or years and then transitioning back, either to the countries from which they came or changing their status into workers. The Coronavirus crisis has further exposed the marginalization of international students in migration research and policy. And this limited visibility is precisely what the Australian Prime Minister has been able to leverage while arguing that foreign students should ‘go home’ as the resource have to be prioritized for Australian citizens.

Yet, international students are and have always been a significant part of higher education. Nationally they constitute an important part of export earnings in some of the major receiving countries, such as the UK. Moreover, the high fees paid by international students often subsidise national students and research funding. And the money they bring into local economies contributes to regional development. Crucially, they also play an important part in knowledge production and circulation - the core business of higher education. They are not consumers but part of the very fabric of higher education, even though this was always ignored.

Yet, international students are and have always been a significant part of higher education. Nationally they constitute an important part of export earnings in some of the major receiving countries, such as the UK. Moreover, the high fees paid by international students often subsidise national students and research funding. And the money they bring into local economies contributes to regional development. Crucially, they also play an important part in knowledge production and circulation - the core business of higher education. They are not consumers but part of the very fabric of higher education, even though this was always ignored.

The coronavirus pandemic has starkly exposed this financial dependence that higher education sector has on high-fee paying international students, with institutions already clamping down on staff recruitment and preparing for the impact of immobility, delayed mobility and interrupted mobility on higher education landscapes. Early indications suggest that many students have dropped their study abroad plans, others have delayed it, while still others are stuck in limbo.

Students were amongst the first to feel the impact of COVID-19. Chinese students, the largest cohort of international students globally, returning from the festive break at the turn of the year were subject to quarantining mingled with an unhealthy dose of racism. Those who returned, then found that they had little ability to return as borders hardened and travel restrictions grew. Those who were wealthy and healthy could return. However, not all international students are wealthy and are able to buy airline tickets at short notice and at inflated prices. They stayed.

The sight of international students queueing in food lines or sleeping rough must surely dispel the notion that international study is all about the privileged.

Indian students, the second largest cohort of international students, such as those in Australia, find themselves in precarious positions with limited means left to support themselves. Many of these students often work in the retail and tourism sectors but now find themselves with either no jobs and income, or in the precarious position of having to work outside of the home. As university accommodation was shutting down everywhere some also lost access to housing.

All these problems haunt their lives as students. Government regulations around minimum face to face attendance can no longer be met as teaching moves online. Study break rules for international students have to be relaxed if they are to accommodate interrupted mobility. Limitations to fieldwork and closure of access to labs will also lengthen the period of study, making study more expensive. In the US, students are no longer able to access the Option Practical Training year – 12 months when they can stay behind and work after a period of full-time study – if they were stuck at home.

When minorities such as Africans in China were found to have been a hub of COVID-19, it led to a resurgence of racism and the hounding of students. The sight of international students queueing in food lines or sleeping rough because they were thrown out of all accommodation must surely forever dispel the notion that international study is all about the privileged.

So how do governments handle those who are already students and stuck? Casting them out and telling them to go home, as the Australian prime minister did, denies the constitutive nature of study to Australian public life. It marks students as neither migrants nor Australian, and therefore removes access to the benefits being offered to those who are deemed to ‘belong’.

But any crisis is also a time of solidarity. A few days after the Australian prime minister’s speech, Melbourne city council announced that they were setting up a hardship fund for international students, a gesture that is being repeated slowly across other countries too. Some countries like Canada and New Zealand have treated all students alike while others like the US and the UK are dependent on university gestures and their separate policies. They have failed to provide a single and striking show of solidarity so necessary in such times.

Facing up to the prospect of not having as many students in the future, worrying about job losses in the sector, recognizing that slashed research funding might be one of the inevitable outcomes of this pandemic is part of the picture of international study in a post-COVID-19 world.

The middle classes who have long borne the brunt of the cost of international study may well be diminished; moreover, where and when each country emerges from this pandemic is also unclear. We will be left with very uneven geographies of international student flows. The imaginations of post-COVID-19 futures must not only hold open the doors for students, but should also shine the torch on the internationalism on which higher education has always depended.

Read the original article on the Open Democracy website

Figure 1: Global Flows of international students 2017; Source: OECD database, credit: @James_W_W

Request your prospectus

![]()

Explore our qualifications and courses by requesting one of our prospectuses today.