What is the future of UN peace operations?

By Georgina Holmes and David Curran

What is the future of UN peace operations and what new research approaches should scholars take to both understand and influence their evolution? These were the central questions academics explored during a two-day international conference entitled Multidisciplinary futures of United Nations peace operations, organised by the BISA Working Group on Peacekeeping and Peacebuilding and the Centre for Global Challenges & Social Justice at The Open University on 20 and 21 February 2023.

Discussions were framed in the context of UN Security Council politics and questions around whether peacekeeping was in decline. It was noted that although Russian aggression in Ukraine was causing tensions within the Security Council, the P5 was still continuing to engage in business-as-usual activities fairly successfully and had renewed four peacekeeping mandates this year, although there is now less appetite within the UN for large-scale peace operations.

Dr Katia Coleman expanded on these issues in her keynote speech ‘Researching peacekeeping in times of crisis’ (source: YouTube), which is available to watch online. She began by explaining how the crisis of confidence in large-scale peace operations within the UN Security Council and a pressure to do more with less, was creating bureaucratic tensions between departments and concern within mission headquarters, resulting in uncertainties for staff, as well as pressures to adapt institutionally.

The depth of contribution from participants and the discussions had at the conference provide some consideration with regards to the future of multi-dimensional peace operations more generally.

- Whatever the future is for UN peacekeeping, it will involve the question, What is UN peacekeeping for?

UN peacekeeping exists for several reasons – from protecting civilians, reducing conflict and halting interstate war to opening up political space, promoting human rights and extending the authority of state. Many missions contain a mix of all the above. The 2015 High Level Panel into Peace Operations noted this, and questioned the suitability of existing ‘concepts, tools, mission structures and doctrine’ for missions which take on a ‘conflict management’ guise, as opposed to peace implementation. With missions facing pushback in all of the areas outlined above, this question is as pertinent as ever.

Linked to this is the issue of legitimacy. The UN has been the lead actor in the field of peace operations for decades. However, alternative models of conflict intervention and management exist and are being implemented by a range of institutions. For example, multi-dimensional peace operations in their current evolution may not adequately resolve the complexities that emerge when terrorist activity enables and feeds off protracted conflict, as observed by Dr Fernando Cavalcante of the United Nations in his keynote talk. This brings to the fore the extent to which the UN is, or is seen to be a legitimate actor by other actors in the peace operations sphere. Dr Sukanya Podder from King’s College London discussed her recently published book ‘Peacebuilding Legacy: Programming for Change and Young People's Attitudes to Peace’ and in her keynote talk called for the need to look back, to reflect on and review what has and has not worked in past missions as well as in peacebuilding initiatives when designing future peace operations. Doing so would ensure missions more adeptly respond to the needs of local communities and better ‘hook into’ existing local cultures and norms to more effectively facilitate peaceful and durable post-conflict transitions. - The future very much depends on how PKOs react to radical upheaval in the past 10 years.

As well as broader structural issues, how the UN responds to more immediate challenges will influence how peace operations move forward. The conference heard of several operational challenges including: the emergence of stabilisation and the role of the Force Intervention Brigade; the impact of climate change; challenges associated with protection of civilians and civilian engagement; the nexus between peace operations and counter-terrorism; the increasing influence of private military and security companies; and addressing criminality and gang violence. Whether these issues are dealt with as ‘outliers’, whereby one-off policy is developed for specific contexts, or whether they will more thoughtfully integrated into mission design may shape the future direction of peace operations. - Peacekeeping will engage with conflict parties in new spaces, and in novel ways.

This relates to the evolution in ways of capturing data; the ways in which the cyber domain has become a theatre of conflict, and the emergence of new technologies for belligerent groups – and peacekeeping actors. This may be a physical manifestation of the ‘future’ but carries with it multiple new ways of working, as well as new dilemmas. Technology will have impacts on issues of regulation and law, open up new avenues to capturing and documenting acts, potentially offering signs of emerging conflicts, and will engage in new non-state actors, such as large technology companies, who have had little involvement in traditional forms of establishing and maintaining peace. - However, what is new may not be new.

Whereas the above point addressed evolution towards the cyber domain, the physical context still contains blind spots which need to be addressed. As long as peacekeeping missions have been deployed, they have shared the space with the local population. However local engagement with peace operations is varied, particularly around how we monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of missions. There therefore are still ways in which the voices of the local population will challenge peacekeeping operations in unprecedented ways. ‘New’ may mean new voices in the room. - UN deployments may be the agents of change for good and for bad.

The conference heard that UN missions themselves are their own agents of change. Decisions made by UN mission leadership, commanders in the field can also move the peacekeeping agenda forward, in addition to diplomats and secretariat officials in UN headquarters in Geneva and New York. However, this may not always be due to positive reasons. For example, the UN’s ongoing experiences regarding neglect, exploitation and abuse have led to significant changes in the peacekeeping system, though more must still be done to address sexual exploitation and abuse as well as gender-based violence, bullying, harassment and workplace discrimination experienced by peacekeeping personnel. - It may not be the UN that shapes the future…

Change can also come from outside agents. The conference discussed the influence of the African Union and on how peace operations may be affected by structural reforms and resource constraints within sub-regional organisations; an enhanced role for NATO in central Europe, and the role of Russian-backed PMSCs in sub-Saharan Africa. In addition, policy will be shaped by how non-institutionalised agents of change such as unarmed civilian peacekeepers, civilian bodies and NGOs on the one hand, and global terrorist movements on the other. These actors could all shape the future as much as a ‘new agenda for peace’.

The future of peacekeeping studies?

Some participants raised concern that peacekeeping research may seem less appealing and relevant to funding bodies in light of recent geopolitical developments. Others noted that charting the future evolution of peace operations is crucial both in terms of understanding how peace and security are affected by geopolitics and for improving operational effectiveness through the investigation of internal mission dynamics and institutional cultures. In sum, peacekeeping and peace operations remain dynamic areas of study requiring multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approaches, while the study of peace operations continues to offer much to the broader study of international relations.

Dr Georgina Holmes is Lecturer in Politics and International Studies, The Open University and Dr David Curran is Associate Professor, Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations, Coventry University.

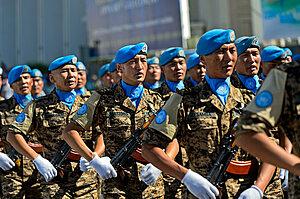

Image: UN peacepeeking battalion parade in Ulaanbaatar. © GFC Collection / Alamy Stock Photo