Does fiction make people more empathic… and is that a good thing?

![Books will sometimes rouse me beyond my nature... / [Dr. Jayne Company]. Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection. Two young boys in classical dress, looking at an oversize book, pointing to the words.](/sites/fass.open.ac.uk/files/styles/large/public/news/books-will-sometimes-rouse-wellcome-collection.png?itok=vZCujLcs)

Author: Rose Turner

Humans are the only animals that create, tell, buy and sell stories, and fiction is big business (Nettle, 2005). The idea that fiction-engagement might be adaptive, functioning to support empathic skills or buffer against a lack of real-world social contact has generated research and public interest over the past decade or so. In 2013, a series of experiments by researchers Daniel Comer Kidd and Emmanuel Castano (2013) were published in the influential Science journal, generating headlines such as “Reading Fiction Makes You A Nicer Person” (Barras, 2013), “Now We Have Proof Reading Literary Fiction Makes You A Better Person” (Schonfeld, 2013), and “For Better Social Skills Scientists Recommend A Little Chekhov” (Belluck, 2013). Actually, the authors made no such claims; they proposed that reading “literary” fiction, as opposed to “popular” fiction supported one particular empathic skill – the ability to interpret the inner mental states of another.

While research in the field grew, so did inconsistencies across the literature, and some studies, including the one published in Science, failed to replicate (though there have been successful replications too). On the other hand, correlational findings have been more convincing, with many studies identifying positive relationships between lifetime fiction exposure and empathic skills. In other words, the more people have read, the better they tend to perform on tasks that measure some of the skills connected to empathy.

So does reading fiction make people more empathic or do more empathic people tend to read more fiction? Increasingly, experimental research does seem to show a causal effect of reading fiction on social skills, but the waters are still quite murky. Which skills are we talking about exactly? And what kind of fiction? Can all fiction be good for us? And is increasing empathy definitely a good thing?

These questions go some way to highlight the complexity inherent to this field of research. Firstly, empathy isn’t just one thing: colloquially it tends to mean putting oneself in someone else’s shoes and sharing in their emotional experience. In Psychology, it can refer to a range of processes from emotion contagion (‘catching’ someone’s feeling), to reading facial expressions, to interpreting someone’s beliefs or motivations. And that’s only half of the picture. Fictional stories can be long or short, engaging or boring, complex and hard to read or easy and straightforward. They might be told in the first, second or third person, be part of any genre, contain dozens of characters or just one that might not even be human. Moreover, stories are increasingly consumed via a range of different media affording different levels of interactivity, including books, TV, radio, immersive theatre, video games, and virtual reality, not to mention short-form social media narratives.

So far, research has generally focused on reading, perhaps, partly, because it’s the most straightforward approach to take to experimental stimuli. However, studies which have used a range of texts to improve generalizability—because a variety of different stories characterises the fiction landscape better than using a single text—have not always accounted for differences between texts statistically, which can lead to false positive results.

And it’s not only important to consider different effects between narrative texts, but also differences across media. Viewing, versus reading, versus interacting with a story could have different and dissociable effects on empathy skills, such as interpreting facial expressions versus sharing another’s emotions. Not only that, but while many people continue to read, more watch TV (e.g., Seddon, 2011) and many engage with other media. In order to present a culturally relevant account of fiction effects, it is essential to address this source of variation in how people engage with stories (for more on the case for exploring other media, see Turner, in press).

So, assuming we get there, and start to identify how fiction—its mechanisms and moderators—can influence different facets of empathy, is this something we would want to cultivate in the real world? Is increasing people’s empathy by exposing them, in some way, to fictional stories, of some kind, always a good thing?

Some scholars argue that increasing empathy could be negative because the distress it generates causes us to turn away from, rather than help, a person in need (Bloom, 2016). But the distress response is only one aspect of empathy that could, theoretically, be influenced by fiction, and other processes may be more likely to lead to altruistic behaviours. Others have pointed out that if we recognise that fiction might support empathy, we have to accept the opposite: that it can also promote stereotypical and dehumanising views (Keen, 2007). That would depend on whether fiction influences empathy by providing social information, which gets internalised and later applied (and that social information could be biased and problematic), or whether the process of engaging with stories—regardless of their content—hones empathic skills which can then be usefully and discerningly applied. As things stand, there is some evidence for both routes to empathy, with more research needed to untangle the mechanisms involved.

Further scientific research exploring the effects of different fiction media affordances would facilitate a more granular interpretation of the fiction-empathy relationship. Moreover, it may usefully bolster anecdotal evidence for the impact of arts interventions across a range of applied settings (e.g., prison reading groups, reading for empathy in schools and arts-based staff training interventions in social care). This is particularly meaningful when empathy in some groups may be on the decline (Konrath, O'Brien & Hsing, 2011) and, meanwhile, the arts and humanities are marginalised in school curricula, and arts and culture threatened by local authority funding cuts.

Find more research at artscog.co.uk.

References

Barras, C. (2013, October 7). Reading literary fiction makes you a nicer person. New Scientist.

Belluck, P. (2013, October 3). For better social skills, scientists recommend a little Chekhov.

Bloom, P. (2016). Against empathy: The case for rational compassion. London, England: Penguin Random House.

Keen, S. (2007). Empathy and the novel. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Kidd, D. C., & Castano, E. (2013). Reading literary fiction improves theory of mind. Science, 342, 377-380.

Konrath, S. H., O’Brien, E. H., & Hsing, C. (2011). Changes in dispositional empathy in American college students over time: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15, 180-198.

Nettle, D. (2005). What Happens in Hamlet? Exploring the Psychological Foundations of Drama. In J. Gottschall & D. Sloan Wilson (Eds.), The Literary Animal (pp. 56-75). Evanston, Il: Northwestern University Press.

Schonfeld, Z. (2013, October 4). Now We Have Proof Reading Literary Fiction Makes You A Better Person. The Atlantic.

Seddon, C. (2011). Lifestyles and social participation [PDF file].

Turner, R. (In press). Fiction, Empathy and the Material World [Advances in Neuroaesthetics: Narratives and Art as Windows into the Mind and the Brain.] Journal for Comparative Literature and Aesthetics, 47, (PDF) Fiction, Empathy, and the Material World. [accessed Apr 19 2024].

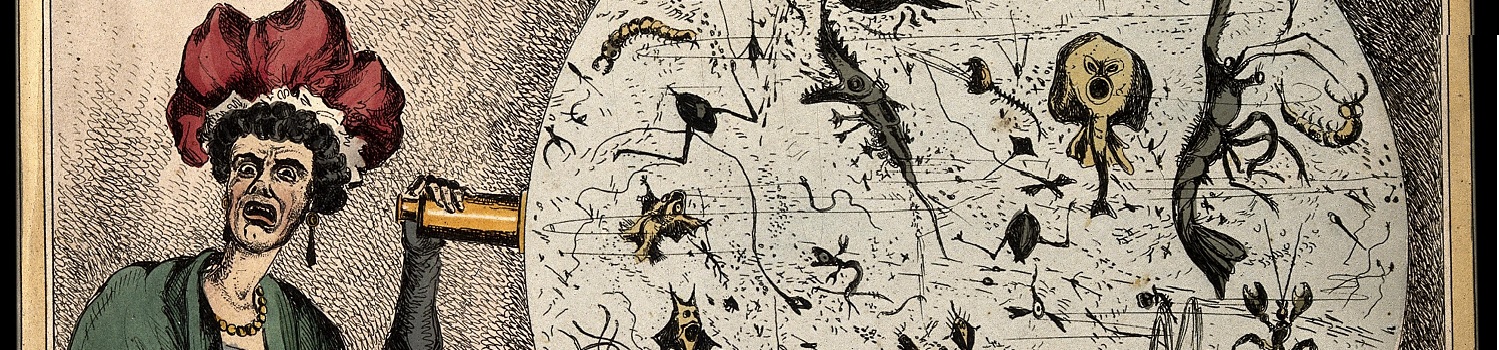

Image insert: Books will sometimes rouse me beyond my nature... / [Dr. Jayne Company]. Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection.