Poetic explorations of illness, disability, love, and loss

Full Sight of Her, my debut poetry collection (published by Black Spring Press, 2020), was released during the pandemic. The focus of the poems is my late partner, Kim Parkinson, who passed away in 2017 from ovarian cancer.

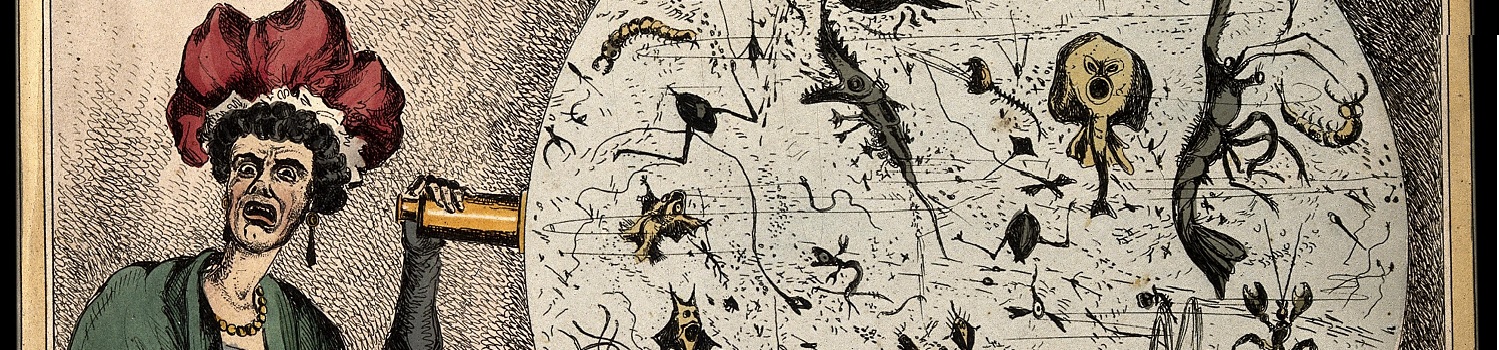

Over our seven-year relationship together, I felt compelled to document the issues that Kim faced, such as prejudice around her visual impairment. For instance, many people she interacted with assumed that she was unable to speak for herself, or they found it inconceivable that she could be an artist, when Kim was, in fact, a highly talented photographer. (Her artwork, as a tribute, can be found interspersed within the book.)

With hindsight, there is also much in the collection that deals with co-morbidity: depression and anxiety (intensified by her blindness), symptoms of perimenopause (which we were both ignorant of at the time), and early signs of what would later develop into an ovarian cyst. Writing of our experiences (admittedly through my own lens) was often cathartic and therapeutic, and the collection draws attention to themes that are often considered taboo, such as hysterectomy and chemotherapy.

While early poems reflected our everyday psychodramas, later poems explored more complex ideas, such as co-dependency, Cassandra syndrome, or premonitions of impending illness. One example is the poem ‘What You Call Your “Winter Mode”’, where I write:

I think of your blood, your bowel, your mother

‘like this her age’, juggling Naproxen and Co-codamol.

I think of your liver, think of your organs, think

still of your brain in its skull as you sleep;

I think of your sunken eye sockets,

the flight of your face in dream.

Likewise, I wanted to chart the often-unspoken sacrifices of a carer, such as myself, especially against the background of an under-funded NHS, where the cared for is caught within the benefits system and social exclusion.

Poems were often written on site – in the cancer ward or in waiting rooms – in a way that managed to skirt voyeurism by way of my partner’s consent and approval, and her belief like me in the power of art to alchemise pain and distress through beauty and transcendence. At the back of my mind was Douglas Dunne’s Elegies, and poets such as Sharon Olds and Pascale Petit, who articulate intense personal trauma. An example of this approach is ‘The Waiting Room’, where I write:

Upstairs, she starts her chemo; down here it’s limbo.

Down here, an anteroom where outpatients mingle.

Everything tinged with the unreal:

from plasma screens to the walls and the vending machine –

its crisps and sweets glint with surplus significance

The nurse offers me watermelon, hands me Allsorts;

the nurse smiles like no angel, a smile unreadable.

Upstairs, a cannula’s attached to her arm. Assistants whisper

and carboplatin gets pumped through the heart’s blood

to zap the cells gone astray since surgery.

Here that’s about all I know, with uncertainty.

No one talks, not even couples beside each other

in the bucket chairs.

Though the ghosts in the empty ones talk. They talk to me.

Reviews were overwhelmingly positive, but placed too much emphasis, for me, on the experience of loss and grief, whereas I read the collection, more than anything, in terms of love and devotion. Moreover, it is a celebration of Kim’s life, her gift of creativity, her courage, and how she continued to flourish despite her difficulties and marginalisation: how society disables.

Helen Ivory writes: ‘These are love poems at their most intense. Poems that celebrate the beloved as an artist with an alchemist’s imagination and bide closely to her through illness in such a deeply affecting way that as a reader, I felt her loss as a palpable ache. The backdrop of this collection is seaside clutter and the impossible metaphysics of plastic chairs, beachside cafes and a dark sea that threatens at the edge of everything to drown even daffodil light with its shade.’

Likewise, Patricia McCarthy asserts that ‘This powerfully moving, even harrowing, collection cuts to the very heart of loss. Yet it also celebrates a very special, strong, sensuous love that over-rides mental illness, an age-gap, and eventual physical illness, leading to the slow death of the beloved.’ She goes on to write that ‘These poems, while honouring his lover for her talent as an artist, her femininity and eccentricity, do not shy away from the graphic. They explore … a world of time present and past, urban landscapes, seasides, claustrophobic interiors, ghosts, different kinds of sight and the liminal, questionable borders between dream and reality in a recognisable world of medicines, mobile phones, and selfies. The haunting final elegy unites all the previous poems and demonstrates achingly “the price of love”.’