Music and Mental Health: historical perspectives

Author: Rosemary Golding

How can music help improve mental health? The question is an important one for modern society, where alongside established forms of music therapy we find singing and drumming groups for mental health in the community and in care homes, musicians visiting prisons and hospital wards, and increasing amounts of research linking musical participation to both wellbeing and intellectual development. With the rise of ‘social prescribing’ as a phenomenon, connecting GPs and other health workers with community activities, music – as well as other arts and pastimes – looks set to become a mainstream part of the health and wellbeing structure in the UK.

Using music to treat mental health conditions isn’t new. Early in the Victorian period, when changes in the social environment led to the establishment of large-scale asylum institutions for the poor across the UK, doctors and management quickly turned to music as the most effective way of offering entertainment to large groups of patients. From the 1830s, the new asylums used concerts and dancing to offer respite from their dull and miserable surroundings, and by the middle of the century most asylums had set up their own band, formed from employees and sometime patients too.

Contemporary written accounts of music in use at asylums offer useful insights into both the kinds of music that were used, and ideas about its influence. One of these, ‘Lunatic Life and Literature’ (1856), discusses the means of curing a patient. The author explains:

‘Music is one grand resource. In most asylums a band of musicians may be selected from the lunatics themselves, wanting only a leader and one or two attendants to organise them and train them to play together, Concerts, therefore, form a chief part of the winter entertainments; and to these may be added dancing – to which, as an exercise for promoting lunatic digestion, (whatever we may think of it as an amusement for people in their senses), we have not the slightest objection – and rural excursions and pic-nic parties.’

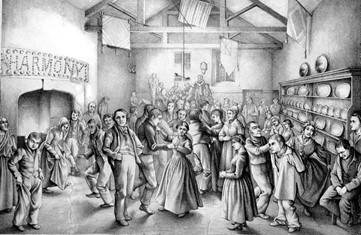

Another, slightly earlier article, focussed on the occasion of the dance. In ‘A ball at a lunatic asylum’ (1845), the author gives an account of an evening at the Morningside Lunatic Asylum near Edinburgh. At this asylum

‘The system pursued… is that of kindness and personal freedom… Occupations and amusements take the place of listless and irksome personal bondage, and the results have been extremely beneficial. Among the most extraordinary, is that which allows of as many patients as may choose, to assemble every Thursday evening, and indulge in the exhilarating exercise of dancing.’

The article describes the ‘order and precision’ in which the dancing is carried out: ‘the ‘band’ struck up an inspiriting reel, and at the end of the first eight bars, the whole of the dancers put themselves in motion, with the promptitude and regularity of a regiment of soldiers.’

Dancing ‘proves not only harmless, but, by diverting their thoughts and senses from the exciting cause of their malady, is a relief and a benefit. This in some measure accounts for the curious fact, that the same patients who are often noisy and obstreperous in their ordinary abodes in the asylum, behave with the utmost decorum at the soirées.’

Patients returned silently to their seats after dancing and resumed their previous level of activity: ‘The excitement they had undergone showed no lasting effect upon them: the stimulant appeared to have acted, as it were, mechanically; for the moment it was withdrawn the patients returned to their ordinary condition. Still, it seems, the meetings are looked forward to with pleasure during the rest of the week. One unhappy inmate is so nearly in a state of dementia, that only two ideas exist within him – the ball on Thursdays, and the chapel on Sundays.’

Here, music and dancing offer respite to the patients, relieving them from the thoughts which are considered to be the cause of their mental illness, and also providing an event to look forward to during the week. The music and dance also provide structure for the events: patients understood how to behave correctly, and practised skills which they would need on return to society.

Find out more about the Music and Mental Health project.